I have a review of Jeff Sebo’s The Moral Circle forthcoming in Ethics, Policy, & Environment. I think it’ll be a while until it sees the light of day, so here’s an excerpt:

There are approximately ten quintillion (10x1018) insects on Earth, and Jeff Sebo talks about all of them … in just over 180 pages. Moreover, we should care about them (to some degree). And not just insects, but other invertebrates and digital beings, including artificial intelligence (AI) systems, whose numbers are potentially limitless. It’s no longer an expanding but an exploding moral circle …, a cosmic bang.

One of the book’s basic premises is that there are some things we know and many we don’t. We know some basic moral principles. We can also estimate many probabilities, with more or less precision—and how confident we are in our estimates affects how we should approach different cases. Uncertainty, instead of paralyzing us, should force us to adopt a flexible framework to determine who and what counts, in what ways, and to what degree. More fundamentally, it is because we don’t know some things that we know that we should treat certain beings better. The explosion of the moral circle is therefore not so much a reflection of our increased knowledge … but of our increased moral caution.

Another basic premise is that many kinds of nonhumans could have moral status. We cannot presume that humans will always take priority; indeed, Sebo will argue they should not. From this and from particular observations about other entities (including probability estimates of the sentience of, say, flies or worms), we can conclude that a whole range of entities matter, from cats and dogs to cuttlefish and honeybees, from chickens and pigs to androids and AIs. At the very least, all of those might matter. And knowing that they might, it’s well-advised to treat them like they do.

The book is a lot of fun, important, and very accessible. You should read it. In this post I’d like to expand on a brief note I make in the review concerning the metaphor of the moral circle, which has been a mainstay of discussions in environmental ethics and animal ethics for decades.

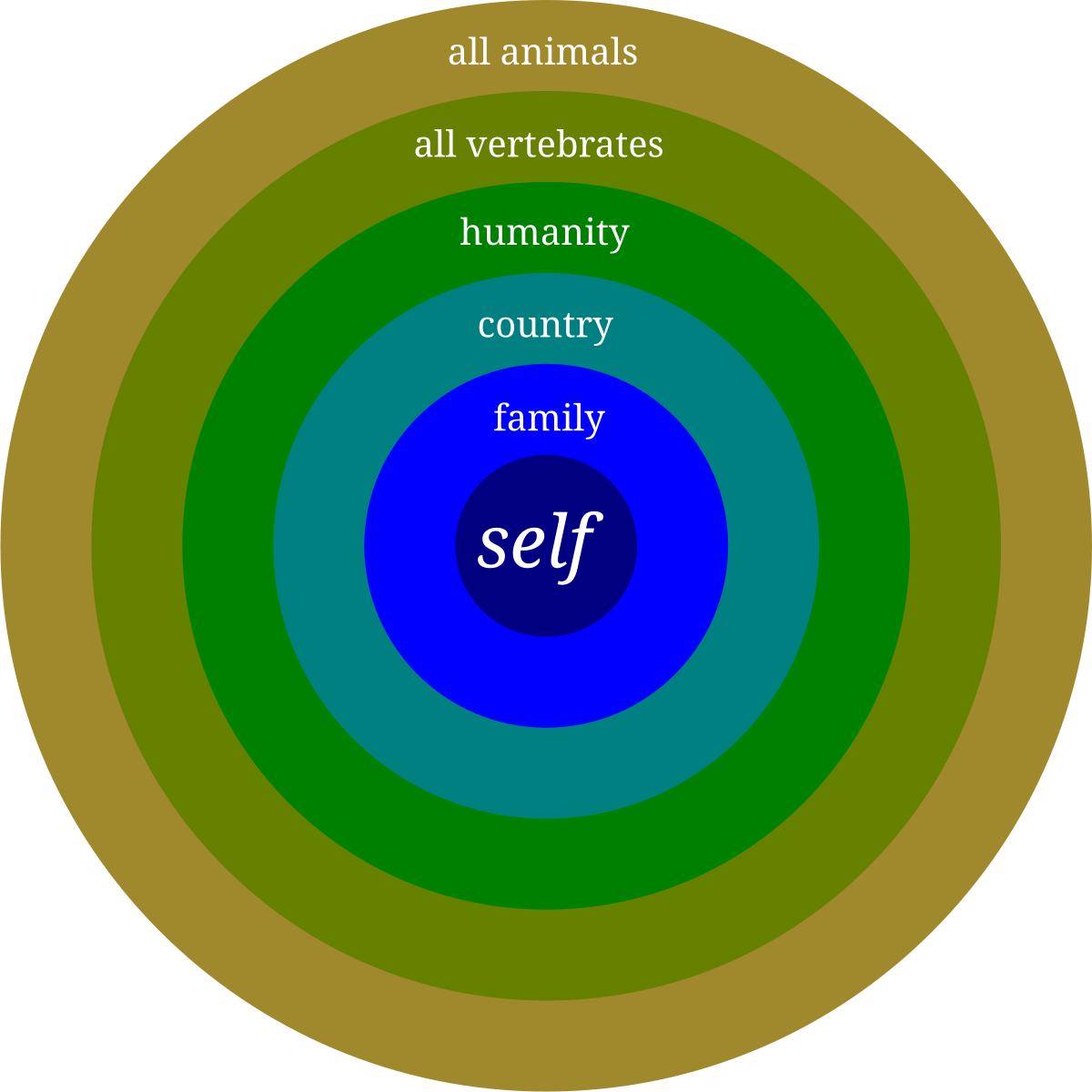

The moral circle is meant to illustrate the structure of the moral community, the set of entities that matter morally in their own right—all the things we morally ought to take into account in our deliberations. Members of the moral community are said to be “morally considerable,” they warrant moral consideration (of their good, welfare, or interests). Who’s in? At the very least, you and I. Very plausibly, cats and dogs, cows, pigs, and chickens. And if you ask me, probably trouts, lobsters, and bumblebees. If you’re biocentrically inclined, you might all living organisms, not just animals. Environmental ethicists typically think in less individualistic terms. The moral community, for land ethicists and deep ecologists, is fundamentally constituted by ecological relationships and systems, wholes over their parts. Species, ecosystems, landscapes, forests, rivers, and maybe the biosphere make up the moral community; their parts matter too, but only because and in virtue of the intrinsic value of the wholes to which they belong. Whichever way we compose the list, we’re naturally inclined to partition nature between beings that are in, that count, and beings that are not, that don’t (tables and chairs, rocks and stars). But it would be bizarre for the community to be like a square or a triangle. Enter the circle.

I find the metaphor inapt for Sebo’s cosmic vision. Let me explain why and propose a new metaphor.

The Moral Circle is a catchy title, and Sebo made the right call in situating his argument in decades of debate about that very idea. The expanding circle has moved, over time, from family to tribe to nation, from nation to humanity, from humanity to nature and other animals, and now might expand to include digital beings. It’s an ancient idea, with roots in the Stoics’ notion of oikeiosis (concentric circles of affinity) and a long history, well before Peter Singer’s 1981 book, The Expanding Circle. Singer’s thesis is that over the course of human history, people have expanded the circle of beings whose interests matter. Originally, that circle would have been limited to self, family, and tribe, but over time it grew to encompass all other humans and then some animals. That’s a descriptive claim about moral progress, but Singer also argues that this tracks progress in moral reasoning, which implies that the circle ought to expand. We’re on the right track.

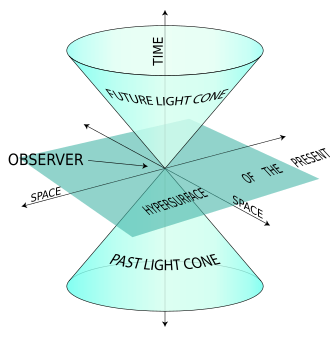

But I don’t think the circle metaphor quite captures what Sebo is arguing for. When we talk about moral circles, we implicitly think about a flat, two-dimensional representation of moral consideration. But why should the moral community be flat? After all, we do not live in two-dimensional space. Moreover, Sebo’s circle contains layers, more like an onion than a pancake. But maybe most importantly, it has no fixed center, and so sphere is hardly a better metaphor. Circles and spheres are uniquely defined by their radius and center point. But what are the radius and center point of the moral circle or moral sphere? Indeed, if part of the argument is that the circle not only does but should expand, it implies at least that its radius is not fixed. Neither, I think, is its center. The basic reason is that we don’t live in three-dimensional space either. We live in a spacetime manifold. What is, then, the best metaphor for the 4D moral manifold? I herewith submit: the moral light cone. The image of a light cone captures the fundamental constraint of moral influence: causality.

In physics, a light cone is the set of all spacetime events that can be causally connected to a given event through light signals. It consists of two parts, as illustrated in the image above. The past light cone contains all the spacetime points from which a light signal could have reached the given event. The future light cone contains all the spacetime points that a light signal from the given event could reach. The boundary of the light cone is formed by photons traveling at the speed of light in all directions. In a spacetime diagram, this creates a cone-shaped surface (or two such surfaces for past and future) with the apex at the original event (or present). The light coneoffers us a picture of the causal structure of our influence in spacetime. (There are things outside the light cone, but they are irrelevant for practical purposes. If you want to change the laws of physics and include those in moral consideration, too, go ahead, but you’d better be quick.)

Why is this a better picture? First, it captures the bounded nature of morality, noted a long time ago by Aristotle in book III of Nicomachean Ethics: we can only deliberate about (and subsequently be responsible for) things we can affect through our actions, or which are under our voluntary control or “up to us.” Our moral influence is bounded by the future light cone. Note that, while we may have obligations to aliens in far-flung galaxies or our descendants in a trillion years, Sebo does not argue we have obligations to extinct dinosaurs, for instance.

Second, the light cone keeps expanding over time because light takes time to travel, so the sphere of theoretically possible causal influence grows at exactly the speed of light. Moral influence, like physical influence, is bounded by causal relationships and expands over time.

Now escaping the strict boundaries of physics and indulging in the metaphor, the moral light cone grows as time progresses, we develop a greater capacity for moral consideration and wider spheres of influence as moral progress marches on. The light cone is finite (as the speed of light) but growing. At any moment, our moral influence is bounded but always expanding, unlike a static sphere.

The aptness of the metaphor does not uniquely apply to Sebo’s framework. Any moral circle is better described as a moral light cone simply because we exist in space time. That’s true even if the circle is fixed—even if the moral community is, say, limited to humans or whites or whatever, and even if it does not change. Our moral influence would still be bounded by the causal structure of our light cone and it would still keep expanding, simply because as time progresses, the scope of our influence grows. Our causal influence expands over time regardless of our moral views. Even the most chauvinistic people have growing influence over time; their actions today can affect more people/places than their actions yesterday could. This is the basic geometric expansion of the light cone. Let’s call this natural expansion.

Sebo is making a stronger claim: that what we thought of as a relatively small and fixed circle should instead be radically expanded in light of uncertainty and many more theories of moral status and of what matters are plausible than anthropocentrism. Let’s call this moral expansion. Sebo’s argument suffices to destabilize the circle. If we adopt the light cone metaphor, Sebo’s argument forces us to conclude that our moral influence is of truly cosmic proportions, extending farther in time and space than we ever thought. Sebo’s last chapter is titled, “Think cosmically, act globally.” We, moral agents, constitute the apex of the cone (formerly, center of the circle), and all moral patients are within it. (Technically, each of us occupies a different light cone, but in practice, they will largely overlap.)

We thus have two parallel kinds of expansion, natural and moral. So how far and how fast can this go? First, the moral light cone is not just bounded in spacetime. It should not include everything. There is such a thing as over-inclusion, for instance based on over-attribution of sentience, agency, or another basis of moral status. We should properly calibrate our expansion to avoid both under- and over-inclusion. If only sentient (or even living) beings have moral status, then the moral light cone should not include ashes and dust, even if that’s what were ultimately reduced to and even if we may have moral (and other) reasons to treat certain samples of ash or dust in respectful or dignified ways (we still would not owe it to the ash or the dust). And even if we end up including AIs, we probably should not include a robot vacuum. None of those things have the morally relevant features warranting inclusion on any plausible theory of moral status.

On a descriptive level, what we can include is also bounded by our abilities and psychology. Think of this as variable moral light speeds. The speed of light (‘c’) sets an absolute speed limit in the universe. If there were even such a thing as a moral speed limit, it seems fair to claim that humanity is still driving well under the limit—Singer’s point in The Expanding Circle was not that we should stop; there’s still much progress to be made, especially concerning animals and distant strangers. Your moral car’s speed is bounded not just by the speed limit but by your engine’s capacity. How fast humanity can expand its moral light cone also depends on technology, for new technologies can amplify reach. Modern social networks collapse physical distance and geographical barriers and allow memes to quickly reach millions. AI systems could someday amplify our influence exponentially, by broadcasting tailored messaging to billions. But moral inclusion itself accelerates expansion. We’ve observed this in the animal protection movement, where simply including animals, first limited to, say, companion and working animals, quickly expanded to billions of factory farmed animals. Caring about fish and invertebrate welfare in food production is slowly going mainstream, too. Wild animal welfare, while not mainstream, is also gaining traction. Inclusion breeds inclusivity. And it is compounded by the inclusion of future beings, affected by climate change and various other present choices and policies. And so on, and so forth.

Different actors also have different reach. A policymaker’s influence can contribute to light cone expansion through institutional leverage. Trendsetters and moral entrepreneurs can also have disproportionate impact. In brief, there is no set speed at which moral expansion happens, though there is a moral speed limit, determined by some fundamental constraints such as attentional limits, causality, and cognitive limitations. So, moral circle expansion is not just about what we include, but about how fast our moral influence can propagate through different media of the moral universe. And for that reason too, I find the moral light cone metaphor more apt.

Great post—and such an illuminating metaphor! (If you’ll forgive my wording…)