It's bleak, man

A tragic vision of nature

There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no real harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment.

— Werner Herzog (Burden of Dreams, 1982)

A few weeks ago, friend of the blog Robert Long brought to my attention clips of Werner Herzog discussing the jungle. The footage, drawn from Herzog’s 1982 documentary Burden of Dreams about the making of Fitzcarraldo, captures the director’s perspective on what he calls the “harmony of overwhelming and collective murder”:

Kinski always says it’s full of erotic elements. I don’t see it so much erotic. I see it more full of obscenity. It’s just… nature here is vile and base. I wouldn’t see anything erotical here. I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and growing and just rotting away. Of course, there’s a lot of misery. But it is the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they sing. They just screech in pain. It’s an unfinished country. It’s still prehistorical. The only thing that is lacking is the dinosaurs here. It’s like a curse weighing on an entire landscape. And whoever goes too deep into this has his share of this curse. So we are cursed with what we are doing here. It’s a land that God, if he exists, has created in anger. It’s the only land where creation is unfinished yet. Taking a close look at what’s around us there, there is some sort of a harmony. It is the harmony of overwhelming and collective murder. And we in comparison to the articulate vileness and baseness and obscenity of all this jungle, we in comparison to that enormous articulation, we only sound and look like badly pronounced and half-finished sentences out of a stupid suburban novel, a cheap novel. We have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no real harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment. [Edited for clarity]

Wonderful.

If you’ve watched Fitzcarraldo or Aguirre, the Wrath of God, you probably know what he’s talking about. Why would anyone not born in the Amazonian jungle risk their life in the pursuit of shaky dreams? And yet they do.

Herzog maintains a distinctly dark and unsentimental view of nature. He sees the natural world as fundamentally indifferent, violent, and chaotic. In Grizzly Man, in a rare instance of explicit judgment, he criticizes Timothy Treadwell’s romanticized view of bears and wilderness, referring instead to nature’s “overwhelming indifference.” There is no harmony in nature. Pretending otherwise is a dangerous illusion. “[C]haos, hostility, and murder,” that’s “the common denominator of the universe.”

Herzog is fascinated by human folly in the face of this indifferent universe—Fitzcarraldo’s or Aguirre’s men dropping like flies, or Treadwell’s ultimate fusion with (consumption by) the bear. Unflinching and unsentimental, Herzog shows us the brutality and the beauty of the world against the vanity of dreams that cannot but be crushed. A sort of cosmic pessimism.

Mill’s nature

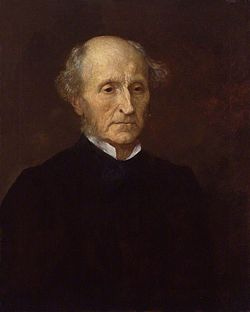

Doesn’t he look happy like a utilitarian? Nature sucks, John Stuart Mill famously… didn’t say. But close enough.

I’m preparing to teach Environmental Ethics again, exploring one of its central tensions: how do we motivate genuine concern for nature while acknowledging that nature is often horrid and indifferent? I talk about John Stuart Mill’s underrated 1874 essay “Nature”, where he argues that “living according to nature” or “following nature” are at best absurd, at worst immoral as practical recommendations. He identifies nature’s fundamental ambiguity:

First, nature as everything governed by natural laws—the totality of phenomena. In this sense, everything is natural: your smartphone, nuclear reactors, human civilization itself.

Second, nature as everything occurring without human intervention—what we usually mean when contrasting “natural” with “artificial.”

Here’s Mill’s dilemma: counseling humans to act according to nature in the first sense is meaningless—how else could they act? But counseling them to follow nature in the second sense proves immoral, because nature displays an overabundance of violence, ruthlessness, and hideous indifference to well-being. As Mill puts it, nature is “callous, ruthless, uncaring, violent, impervious to our sentiments of justice and fairness.” Also: “The workings of the non-human world are full of things that would be deemed the greatest crimes if men did them.” Predators tear apart prey while still alive. Natural disasters kill indiscriminately. If you chose to act like nature—causing massive suffering without regard for individual welfare—I would consider you not a Nietzschean Übermensch but a monster. Mill’s aim isn’t to vilify nature but to show that human civilization exists precisely to improve upon it, not mindlessly follow it.

Mill’ essay is a great way to teach students about the fallacy of the appeal to nature, which infers from the claim that something is natural (or unnatural) that it is thereby good (or bad).

This is, of course, too crude. There are ways of following nature that do not run afoul of Mill’s dilemma, when “follow” and “nature” are properly construed. I do not believe that Stoicism, Spinozism, or Daoism are either absurd or immoral doctrines. Still, more work is needed before you can take nature as your blueprint and live the good life.

Nietzsche, who didn’t like English utilitarians all that much, echoed Mill’s insights, knowingly or not. First, in The Gay Science:

Let us beware of thinking that the world is a living being. … The astral order in which we live is an exception; this order and the considerable duration that is conditioned by it have again made possible the exception of exceptions: the development of the organic. The total character of the world, by contrast, is for all eternity chaos, not in the sense of a lack of necessity but of a lack of order, organization, form, beauty, wisdom, and whatever else our aesthetic anthropomorphisms are called. Judged from the vantage point of our reason, the unsuccessful attempts are by far the rule; the exceptions are not the secret aim, and the whole musical mechanism repeats eternally its tune, which must never be called a melody. … When will all these shadows of god no longer darken us? When will we have completely de-deified nature? (§109, trans. Josefine Naukhoff and Adrian Del Caro)

Then, more explicitly aimed at the Stoics, Beyond Good and Evil, in which Nietzsche calls the Stoics’ command to live according to nature “a fraud”:

Imagine something like nature, profligate [and] indifferent without measure, without purpose. … How could you live according to this indifference? Living—isn’t that wanting specifically to be something other than this nature? … Assuming your imperative to “live according to nature” basically amounts to “living according to life”—well how could you not? … In fact, something quite different is going on: while pretending with delight to read the canon of your law in nature, you want the opposite. … Your pride wants to dictate and annex your morals and ideals onto nature. … For all your love of truth, you have forced yourselves so long, so persistently, and with such hypnotic rigidity to have a false, namely Stoic, view of nature, that you can no longer see it any other way. (§9, trans. Judith Norman)

Stoicism, for Nietzsche, faces something a bit similar to Mill’s dilemma. Suppose virtue consists in “living according to nature.” If nature is irrational and chaotic, then what good is it to make a virtue of following it? If, on the other hand, nature is inherently normative, this is owing to a teleological conception that Nietzsche and naturalists reject. Nature is not governed by reason. Nietzsche attributes the latter, anthropomorphic view to the Stoics.

Nature sucks. So why protect it?

The challenge requires defining two things: the scope of what matters in nature and the range of attitudes that warrant our attention. It may be that some non-instrumental, non-exploitative, non-destructive attitude—care, admiration, reverence, respect—will be warranted towards just about everything in nature. I’m not comfortable stipulating that any particular thing or process in nature fails to commend at least some minimal form of non-purely instrumental valuing attitude. Predation, illness, decay, sediments, magma, toxic gases, invasive plants? Could it be that they warrant something like awe, curiosity, or humility—attitudes that imply, if only tacitly, something other than a preference for destruction or commodification?

“Nature” in its broadest Millian sense proves too capacious if it includes everything that exists according to natural laws. But of course, that’s not what we typically mean by nature. Mill is absolutely right that following nature is terrible advice. But “don’t mindlessly destroy or despise nature” is different, and nothing in Mill’s argument suggests otherwise. From experience, Mill has never dissuaded my students from caring about the environment. So there's that.

Mill lets us see that nature is, as Tennyson famously put it, “red in tooth and claw”, and that is not all well and good. We must improve on nature. If, like Mill, you are a utilitarian, we must change nature to reduce the suffering and promote the happiness of all sentient creatures.

Interventionism

The wild animal suffering literature takes these facts as a call to action. Philosophers like Oscar Horta, Catia Faria, Kyle Johannsen, and many others acknowledge nature’s horror, dismissing the “idyllic view of nature,” and argue that this creates moral obligations to intervene. Our aim should be, in the words of Martha Nussbaum in Frontiers of Justice, “the gradual supplanting of the natural by the just.” Consider the reality:

In the deep snows the deer lies starving. Its ribs show stark beneath the matted hide, the belly hollow as a drum. For days it has not moved save to lift its head at sounds that might mean nothing. The snow packs around its legs like a tomb. Each breath costs more than the last. There is no rescue coming. There is no spring.

The ichneumon wasp has made of the caterpillar a living larder. The eggs hatch and the larvae begin their feeding, consuming the host from within while keeping it alive—alive and aware. Week by week they devour the organs in careful sequence, saving the heart and brain for last. The caterpillar continues to eat, to move, to feel the devourers working inside its body. This is not metaphor. This is Tuesday in the natural world.

The pox swells around the bird’s eyes until they seal shut. Tumors bulge from its beak until it cannot open to feed or drink. The bird sits on its branch in permanent darkness, slowly dying of thirst with water just beyond its reach. It will take days. There is no purpose to this suffering, no lesson, no meaning. Only the facts: blindness, thirst, death.1

To state the brute facts: these animals are dying a slow and painful death.

Wild animal welfare advocates accept something like Herzog’s descriptive view but reject his tragic acceptance. It is instead a call to action: herbivorize predators, engineer trophic chains, pave the forests! If nature truly contains this much suffering, doesn’t intentional concern for trapped beings become more significant, not less? Herzog’s cosmic pessimism doesn’t negate the reality of individual animal suffering; it might instead provide the strongest possible argument for why that suffering matters morally. For a variety of reasons (see e.g. this, that, and that too), I am not quite ready to endorse this move, but I see the appeal.

Herzog might crush such aspirations as another form of dangerous romanticism. The interventionist aspirations may be just an inverted form of idyllism. Where Timothy Treadwell romanticized nature as harmonious and loving, wild animal welfare advocates might be romanticizing our capacity to meaningfully reduce cosmic suffering. Herzog would probably see both as forms of hubris, failing to grasp the true scale and intractability of the forces we’re dealing with.2

In Encounters at the End of the World, his 2007 documentary about Antarctica, Herzog asks a local penguin expert about “deranged” or “insane” penguins. Penguins can be “disoriented”, the scientist replies. In the next scene, Herzog observes a lone penguin parting from his group (3’58” in the clip), and experts’ advice and a nearly universal (albeit oft-violated) presumption against interference among ecologists:

The rules for the humans are: do not disturb or hold up the penguin. Stand still and let him go on his way. And here, he’s heading off into the interior of the vast continent. With 5,000 kilometers ahead of him, he’s heading towards certain death. (5’01”)

This is a heartbreaking passage. There is nothing “good” about the penguin’s certain death. It serves no purpose. Tragically, even if we had allowed ourselves to intervene, this would have been in vain, for we were told that such penguins inevitably return to their fateful destination. The penguin was doomed by whatever force of nature inhabited him.

In Encounters, Herzog expresses ambivalent attitudes toward environmentalism. He deplores a certain obsession with conservation:

It occurred to me that in the time that we spent with him [a scientist] in the greenhouse possibly three or four languages have died. In our efforts to preserve endangered species we seem to overlook something equally important. To me, it’s a sign of a deeply disturbed civilization, where tree-huggers and whale-huggers in their weirdness are acceptable, while no one embraces the last speakers of a language.

At the same time, he notes:

[O]ur presence on this planet does not seem to be sustainable. Our technical civilization makes us particularly vulnerable. There is talk all over the scientific community about climate change. Many of them agree, the end of human life on this earth is assured. Human life is part of an endless chain of catastrophes, the demise of the dinosaurs being just one of these events. We seem to be next.

Thanks for the cheerful note, Werner.

From cosmic pessimism’s perspective, interventionism is like trying to bail out the ocean with a teacup—a dim light against the darkness but ultimately a cosmetic attempt to replace the “harmony of overwhelming and collective murder” and bridge the gap between human aspirations and cosmic reality. We might help some individuals locally and fix the human infrastructures that cause so much unnecessary suffering,3 but we’ll never address the deep structures of reality generating suffering. Herzog shows no shortage of praise for the admirable qualities—determination, idealism, nobility, kindness—displayed by his characters. But he is under no delusion. Aguirre’s dreams of empire were always meant to be consumed by the jungle. Treadwell was never going to save the bears, who didn’t really need saving to begin with.

Outer dark

Recently, I’ve been reading through Cormac McCarthy’s corpus while catching up on Herzog’s classics.

Both men share a clear-eyed, pessimistic, yet deeply poetic view of nature.4 Too bleak for my students, though some of them must have read The Road, and they’re exposed to doom nonstop. But I rely on Mill’s essay for its cleansing power. It rids them of romanticized conceptions and forces the question: Why exactly should I care about this [waves at all the horror taking place in nature]?

Throughout their work, McCarthy and Herzog express horror at the destruction we’ve wrought upon ourselves and upon the nonhuman world. If I do my job well, they experience the tension: nature is horrid yet beautiful, cruel and indifferent yet worth protecting, powerful yet vulnerable.

Nature is all of the following: the ruthless desert of McCarthy’s Southwest, the abominable jungle of Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, the supervolcanoes that might wipe us out from the face of the earth, the creatures we wantonly harass, exploit, and destroy, the fences we erect to close the commons, and the ungodly energies we have extracted from the atom to erase, on a whim, whole populations and landscapes.5

One conviction I’ve taken from Herzog and McCarthy: there is infinite beauty in the world’s bleakness and darkness. Anyone reading Suttree, All the Pretty Horses, The Crossing, or Blood Meridian must realize this. Consider this passage from All the Pretty Horses:

That night he dreamt of horses in a field on a high plain where the spring rains had brought up the grass and the wildflowers out of the ground and the flowers ran all blue and yellow far as the eye could see and in the dream he was among the horses running and in the dream he himself could run with the horses and they coursed the young mares and fillies over the plain where their rich bay and their rich chestnut colors shone in the sun and the young colts ran with their dams and trampled down the flowers in a haze of pollen that hung in the sun like powdered gold and they ran he and the horses out along the high mesas where the ground resounded under their running hooves and they flowed and changed and ran and their mains and tails blew off of them like spume and there was nothing else at all in that high world and they moved all of them in a resonance that was like a music among them and they were none of them afraid horse nor colt nor mare and they ran in that resonance which is the world itself and which cannot be spoken but only praised.

These are not the words of a nihilistic writer. People often mistake McCarthy’s pessimism for nihilism. This beauty has a cost. All the Pretty Horses again:

and he felt a loneliness he’d not known since he was a child and he felt wholly alien to the world although he loved it still. He thought that in the beauty of the world were hid a secret. He thought the world’s heart beat at some terrible cost and that the world’s pain and its beauty moved in a relationship of diverging equity and that in this headlong deficit the blood of multitudes might ultimately be exacted for the vision of a single flower.

As Alicia notes in Stella Maris, “The world has created no living thing that it does not intend to destroy.”

Yet consider these other gems:

In The Passenger, Bobby Western, Alicia’s brother, watches his friend Debussy disappear among tourists: “He watched her until she was lost among the tourists. Men and women alike turning to look after her. He thought that God’s goodness appeared in strange places. Don’t close your eyes.” This echoes Tobin the ex-priest’s words in Blood Meridian: “For let it go how it will, he said, God speaks in the least of creatures. The kid thought him to mean birds or things that crawl but the expriest, watching, his head slightly cocked, said: No man is give leave of that voice.” It is both, of course: the vilest men and the lowliest creatures all echo God’s voice.

John Sheddan, “The Long One”, in The Passenger (modeled on McCarthy's real friend), says: “Suffering is a part of the human condition and must be borne. But misery is a choice.”

In the NPR conversation, McCarthy said:

Well, some of my friends would probably tell you that making me pessimistic would be a difficult chore indeed. But I’m pessimistic about a lot of things. But as Lars has quoted me as saying, there is no reason to be miserable about it. (NPR, Science Friday, April 2011)

Yes.

These three examples were edited by Claude Sonnet to capture the essence of McCarthy’s and Herzog’s vision. I also used Claude to edit my post for spelling, grammar, and turns of phrase.

For more optimistic views of life in the wild, see Heather Browning and Walter Veit’s work and Peter Godfrey-Smith’s recent book, Living on Earth.

I really mean this. One of my ongoing projects is focused on urban animal welfare (see e.g. this video). I also want to put a plug for the great work done by Wild Animal Initiative. It’s all doom and gloom, but some people are really trying.

Herzog and McCarthy gathered for an episode of Science Friday in 2011 with Ira Flatow and Lawrence Krauss. I cannot recommend Krauss’s contribution, but the confluence of Herzog and McCarthy is nothing short of amazing. Stay until Herzog’s reading of an excerpt from All the Pretty Horses.

Some has been written, and a lot more could be, about McCarthy’s quasi-environmentalist thought, running through his work from The Orchard Keeper to Blood Meridian and from the Border Trilogy to The Road. McCarthy was influenced by, admired by, and/or interacted with the likes of Annie Dillard, Bruce Chatwin, Edward Abbey, Barry Lopez, and Roger Payne.

Great piece. I have two notes

1. First of all, the line between an objective view of nature (putting aside whether a truly objective nature exists) and philosophical pessimism exists but I find it extremely fascinating how Herzog, based on the quotes you have put in here, seems to cross over this threshold so quickly that if you aren't looking it appears to not even exist. He goes from "hard truths in life" to an intense Schopenhauerian perspective. Frankly I find philosophical pessimism exactly what Christians warned about when they spoke of what the "demonic" was. (Also relates to why they rejected Gnosticism so much). Again, this line between nature being "objectively cruel" and it just being "evil", as Herzog seems to imply, exists and we shouldn't forget it. At least the way I see it, the first perspective is more concerned with truth (though objectivity as ontology and epistemology to begin with is on shaky ground especially in regards to nature. Terrence McKenna really comes to light here), while the second perspective is more concerned with a feedback loop of its underlying assumption. Pessimism versus optimism is nothing but a feedback loop of an underlying assumption. (reinforcing an optimistic point of view versus a pessimistic point of view)

Second of all, I couldn't help but think of my own related idea while reading this. I think its likely that from a Nietzschean perspective, we deeply resent nature. Nature was our master, and we adopted a sort of "slave morality" towards it, conceptualizing it as "evil". This resentment turns into desire to control nature and this explains why we are wrecking the planet. An incredibly neurotic condition indeed. But nature is indifferent. It doesn't care about us. We are slowly matching it in power but in many ways it is still more powerful than us (again how nature is defined is important here). Its a weird idea but I think it highlights our neurotic dysfunction with nature as a whole and why we cannot seem to get a grip on our problems with it and why we are still causing so much damage. In the darkest deepest subconscious, I think most people actually want to destroy nature. They deeply desire to gain control back and punish that which has caused us immense pain and suffering (again the resentment response). If we're being honest, if we actually had an okay relationship with nature, we would not be wrecking the planet. But nobody wants to admit that. and that's pretty dark.

It sounds like Mill had a complicated relationship with his mother.