Mozart is the greatest, they say

In my last Mozart installment, I wrote:

Not everything great composers have said is worth taking at face value. But when patterns emerge, it’s worth paying attention. It would be bizarre for many great minds to be completely wrong about the same thing. Not impossible, but unlikely. Likewise, aesthetic testimony is not always reliable. Indeed, much of it is probably not worth much. Experience art for yourself, don’t just trust the experts! But under the right circumstances, we learn something from aesthetic testimony. And I think that nearly two centuries’ worth of great minds saying great things about Mozart tells us something about Mozart.

Some of the greatest composers of the two previous centuries were admirers of Mozart. And while a great composer does not a great critic make (nor vice versa), most of them quite obviously had great taste. They may not be ‘ideal critics’ (in Hume’s sense) but composers have often had better judgment than actual critics of the time. Beethoven, Brahms, and Mahler got a lot of bad reviews; contemporaneous composers understood better what they were up to. The most influential music critic of the 19th century was not too shabby a composer himself—Robert Schuman—and was early recognizing Brahms’s genius in his famous 1853 “Neue Bahnen” (New Paths) article in Neue Zeitschrift. Brahms was only 20.

If many of the greats are closer to ideal critics than many actual critics, and their judgments have converged and remained stable over time, they may be onto something. And that something, I claim, is Mozart’s supreme, enduring greatness. (Of course, the fact that classical musicians continue to perform, conduct, and record Mozart so much is also some defeasible evidence—it is, however. confounded by Mozart’s popularity, which itself may not be sufficient evidence of greatness.)

Haydn was the focus of the previous post. Today, I will highlight some of Mozart’s greatest admirers in the Romantic and post-Romantic periods. This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive collection or representative of what the Greats thought of Mozart—you will find many more apocryphal and some presumably authentic quotes online. It’s an unabashedly biased sample. Some of the following quotes and anecdotes are sometimes difficult to trace to their primary source. I don’t think any of them are myths, but some may be apocryphal, and I didn’t always do my due diligence and retrieve the primary source unless it was easy. So, take what follows with a grain of salt.

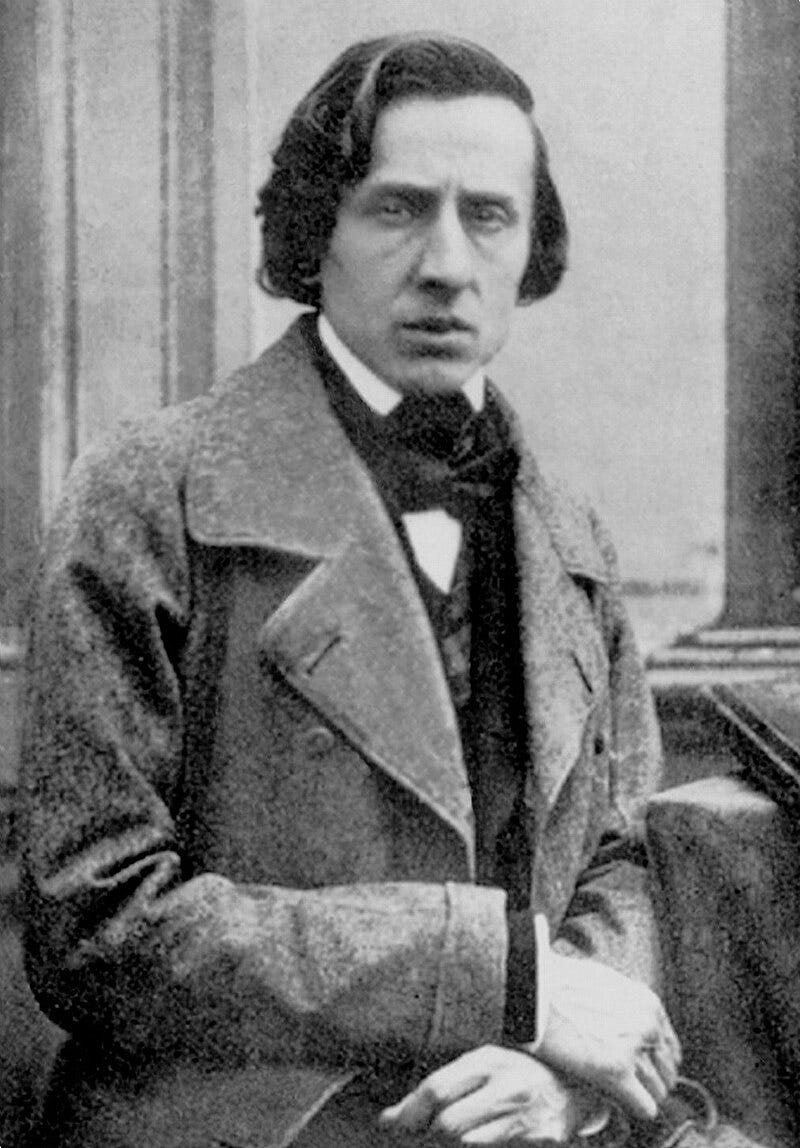

Frédéric Chopin is said to have requested at his deathbed that Mozart be played. According to an early biographer,

The reverent admiration which Chopin had always felt for Mozart led him to request, in his last days, that no music but the German masterʼs sublime Requiem should be performed at his funeral. Up till 1849 women had not been allowed to take part in the musical performance at the Madeleine Church, and special permission had to be obtained from the ecclesiastical authorities. On this account the funeral did not take place till October 30th. The first artists in Paris cooperated. The funeral march from Chopinʼs B flat minor Sonata, which had been scored by Reber for the occasion, was introduced at the Introit. For the Offertory, Lefébure Wély played on the organ Chopinʼs Preludes in B minor and E minor. The solos of the Requiem were rendered by Mesdames Pauline Viardot-Garcia and Castellan, and the famous bass singer, Lablache, who gave a splendid delivery of the “Tuba mirum.” Meyerbeer conducted, and the pall-bearers were Prince Alexander Czartoryski, Delacroix, Franchomme and Gutmann. (Karasowski, p. 320)1

Now, you might think, Mozart’s Requiem at your funeral, that’s cliché. You would be wrong.

Backtracking just a little, his last concert began with one of Mozartʼs trios, before playing his own work, including his new cello-sonata in G minor (op. 65). (Karasowski, p. 309, n, 43) Chopin is of course best known for his piano works. He wrote very few orchestral pieces. One of them is Variations on “Là ci darem la mano”, op. 2 (the aria from Don Giovanni). This was Chopin’s first work for piano with orchestra, written in 1827 when he was 17.

Chopin then went on to write two piano concertos and three concertante pieces but otherwise neglected the orchestra. That one of his very few, and the first, of his orchestral works should be an homage to Mozart’s melodic and operatic gifts may just be a coincidence (but I don’t think so).

Educated by German masters and on German principles, Chopin had a decided preference for the music of that country. Handel, Gluck, Bach, Haydn, and Mozart were his ideals of perfection; and although he felt the spell of Beethovenʼs genius, he had less sympathy with its gigantic conceptions than with the fascinating charm and lovely melodies of Mozartʼs compositions. There seemed to him in Beethovenʼs works a want of delicate finish, the proportions were too colossal, and the storms of passion too violent. About the year 1835, Schubert began to be known in Paris, principally by his songs. Like all impartial musicians, Chopin was charmed by their wealth of melody; but he regretted that in his larger works, the exuberance of the composerʼs fancy frequently led him to overstep the limits of form, and thus impair the effect. (Karasowski, p. 330)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s diary entry for 20 September/2 October 1886 reads as follows:

I bow before the greatness of some of his works, but I do not love Beethoven. My attitude towards him reminds me of how I felt as a child with regard to God, Lord of Sabaoth. I felt (and even now my feelings have not changed) a sense of amazement before Him, but at the same time also fear. He created heaven and earth, just as He created me, but still, even though I cringe before Him, there is no love. Christ, on the contrary, awakens precisely and exclusively feelings of love. Yes, He was God, but at the same time a man. He suffered like us. We are sorry for Him, we love in Him His ideal human side. And if Beethoven occupies in my heart a place analogous to God, Lord of Sabaoth, then Mozart I love as a musical Christ. Besides, he lived almost like Christ did. I think there is nothing sacrilegious in such a comparison. Mozart was a being so angelical and child-like in his purity, his music is so full of unattainably divine beauty, that if there is someone whom one can mention with the same breath as Christ, then it is he. [...] It is my profound conviction that Mozart is the highest, the culminating point which beauty has reached in the sphere of music. Nobody has made me cry and thrill with joy, sensing my proximity to something that we call the ideal, in the way that he has [...] In Mozart I love everything because we love everything in a person whom we truly love. Above all I love Don Giovanni, as it was thanks to this work that I found out what music is. Until then (till the age of 17) I had known nothing apart from pleasant Italian semi-music. Of course, whilst I do love everything in Mozart, I won't claim that every minor work of his is a masterpiece. No! I know that any one of his sonatas, for example, is not a great work, and yet I love every sonata of his precisely because it is his – because this musical Christ touched it with his radiant hand.2

Tchaikovsky wrote a lot about Mozart and also arranged, adapted, quoted, or wrote variations on his music a lot too:

Ave Verum Corpus, motet (KV 618) — arranged for orchestra as the third movement of Tchaikovsky's Suite No. 4, Op. 61 ("Mozartiana") (1887).

Eine kleine Gigue for piano (KV 574) — arranged for orchestra as the first movement of Tchaikovsky's Suite No. 4, Op. 61 ("Mozartiana") (1887).

Fantasie in C minor (KV 475) — music used in Tchaikovsky's quartet Night (1893).

Idomeneo , ballet music from the opera (KV 367) — alterations to the Chaconne and Gavotte for a concert performance (1889).

Le Nozze di Figaro, opera buffa in 4 acts, KV 492 (1786) — Tchaikovsky translated and edited a new Russian edition of the score (1876).

Menuett for piano (KV 355) — arranged for orchestra as the second movement of Tchaikovsky's Suite No. 4, Op. 61 ("Mozartiana") (1887).

Variationen für Klavier über "Unser dummel Pöbel meint" aus Gluck's "Die Pilger von Mekka" for piano (KV 455) — arranged for orchestra as the fourth movement of Tchaikovsky's Suite No. 4, Op. 61 ("Mozartiana") (1887).

Johannes Brahms, one of my favorite composers, loved Mozart and Haydn. Brahms wrote variations on themes by Handel, Haydn, and an arrangement for the left hand of Bach’s Chaconne for the Violin Partia, No. 2, but not Mozart. And it is Beethoven’s shadow, not Mozart’s, that loomed over Brahms for much of his career (at the very least until he completed his First Symphony). Still, Brahms may have admired no composer more than Mozart, especially in his late years (again, what’s with the end of composers’ lives and Mozart). Here is what he thought of Mozart’s Piano Concerto, No. 24 in C minor (K. 491), one of his greatest concerti and one of only two in a minor key with No. 2 in D minor: “a masterpiece of art and full of inspired ideas.” He encouraged Clara (Wieck) Schumann— Robert’s wife, Brahms’s lifelong platonic love, an excellent composer in her own right, and one of the greatest pianists of the 19th century—to play it.3 She made it part of her repertoire and wrote a cadenza for the first movement. So did Brahms. The overlap between their respective cadenzas is apparently a matter of dispute. These days pianists perform most often Beethoven’s or sometimes their own cadenza.

Brahms also compared Mozart with Beethoven to the latter's disadvantage, in a letter to Richard Heuberger, in 1896: “Dissonance, true dissonance as Mozart used it, is not to be found in Beethoven. Look at Idomeneo. Not only is it a marvel, but as Mozart was still quite young and brash when he wrote it, it was a completely new thing. You couldn't commission great music from Beethoven since he created only lesser works on commission—his more conventional pieces, his variations and the like.”4

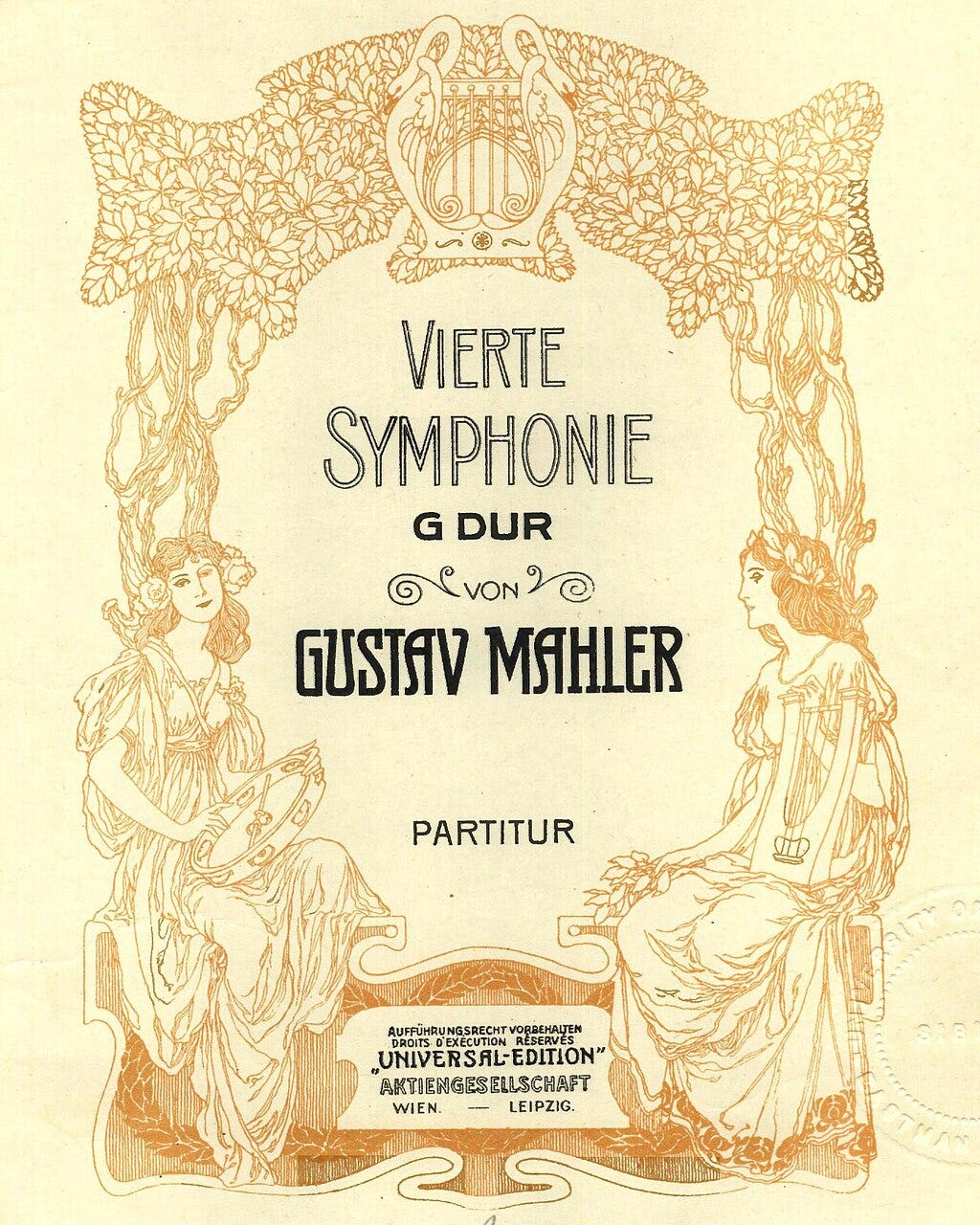

“Mozartl!” (little Mozart). That is, at least according to Gustav Mahler’s notoriously unreliable widow, Alma—what Mahler said as he expired on his deathbed. Mozart’s operas had been a staple—and source of recognition—of Mahler’s career as a conductor. He helped put his operas at the core of the repertoire from then on—not that they were ever forgotten or neglected, mind you. Even granting that Alma correctly reported her husband’s last word, it remains enigmatic. Mahler’s songs and symphonies do not exactly sound very Mozartian—except maybe for his Fourth, arguably his most accessible and classical, shorter and more compact (including orchestra-wise) than his previous and subsequent symphonies. Both Mozart and Mahler did things with the human voice that few other composers would do, and both of course contributed in immense ways to Vienna’s stature as the capital of the Austro-German tradition in classical music, a tradition Haydn and Mozart consolidated and perfected, and which Mahler crowned and brought to the brink. Despite the musical gap separating the two composers, Mahler’s continuous love and admiration of Mozart seems genuine.

But you may wonder, What’s up with composers whispering Mozart’s name on their deathbed? I do too, but I can think of worse ways to die.

Except for himself, Benjamin Britten recorded Mozart more than any other composer. The 20th-century British composer recorded Mozart’s middle and late symphonies, serenades, his greatest piano concertos, and his opera Idomeneo. As one of the most important opera composers of the century, Mozart’s influence on Britten was no doubt powerful. Mozart remained, throughout Britten’s life, the summit of music. Maybe apocryphal, but Britten reportedly told the actor David Spenser who was raving about Romantic composers: “One day, David, you will realize that Mozart is the greatest composer that has ever lived and that Brahms is easily the worst.”

Now, I have to mention that Britten was known for his strongly held and unpopular opinions about other composers. To wit, he strongly disliked Brahms (though not as a teenager) and favored Mozart over Beethoven. He went so far as to say: “I play through all Brahms every so often to see if he’s as bad as I thought — and usually find him worse.” He found Brahms’s First Symphony (to me, one of the greatest symphonies of all time) “ugly and pretentious”. And he famously quipped, “It’s not bad Brahms I mind, it’s good Brahms I can’t stand.”5 Make what you will of those pronouncements (he also found the second movement of Beethoven’s last piano sonata “grotesque”). The puzzle is how he could be wrong about Brahms and Beethoven while being right about Mozart!

What I find fascinating is that none of these composers sound like Mozart at all. They never tried to emulate or imitate him. They were writing completely different music. Not being a musicologist, there is surely a lot of structural similarities I am missing. I can see how Mozart’s operas influenced some of these composers, most notably Mahler and Britten. I can sense both Mozart’s and Mahler’s sense and appreciation of the tragic. I can also see how Mozart, being the epitome of classicism, shared with Brahms, well, his classicism, and ability to push the envelope while remaining within the standard forms of the classical era. And Mozart’s unmatched melodic genius (barring Schubert) is echoed in Chopin’s nocturnes. But these connections are loose, at least to the ear. What I think those composers are hearing in Mozart instead, and what makes them great composers in their own right, is an intrinsic desire to make great music just because they could.

Previous installments

Haydn's Mozart

This is the first installment in my series, “Great people saying great things about Mozart.” (See my prelude.)

The greatest, prelude

Tyler Cowen says classical music “is one of the world’s greatest gifts to you, and essentially free.” I’m not entirely sure about that last part, but he is right that, as long as you have access to music, classical music is cheap, and probably much ch…

Moritz Karasowski, FREDERIC CHOPIN: HIS LIFE, LETTERS, AND WORKS, translated from German by Emily Hill, London: William Reeves, 1879. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/46573/46573-h/46573-h.htm

On Tchaikovsky and Mozart, see the incredible wiki, Tchaikovsky Research: https://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/pages/Wolfgang_Amadeus_Mozart

Source: Wikipedia, citing Wen, Eric, “Enharmonic transformation in the first movement of Mozart's Piano Concerto in C minor, K. 491”. In Hedi Siegel (ed.). Schenker Studies: Symposium: Papers. New York: Cambridge University Press. Wen translates from Richard Heuberger, Erinnerungen an Johannes Brahms, Tutzing, 1971, p. 93. The original quote was: “ein Wunderwerk der Kunst und voll genialer Einfälle”.

Source: Wikipedia, citing Fisk, Nichols, Josiah, Jeff (1997). Composers On Music: Eight Centuries of Writings. University Press of New England. pp. 134–135.

Source: Jonathan Gaisman, “Brahms: sublime genius on a major scale”, The Critic (2023). https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/june-2023/brahms-sublime-genius-on-a-major-scale/