Publishing Without Romance

A Public Choice Analysis of AI-Restrictive Policies

Happy New Year!

What follows is a theory I’m not sure I endorse. It may be too cynical to be true.

In 2018, I was fortunate to audit Saul Levmore’s Public Choice at the University of Chicago Law School, a hotbed of law and economics. One insight I took away: When considering any regulation or policy, we can ask, whose interests does it serve? Who stands to benefit from shaping market forces and social behavior more broadly?

Sometimes, the answer is the public interest. Sometimes it’s simply what voters want, and in a democracy, lawmakers ought to honor the people’s will. In most such cases, which one hopes would cover most policymaking, rules coordinate behavior and align incentives with desired social outcomes. The core insight of public choice theory comes from economics: incentives matter. People respond to incentives, so even legislation aimed at promoting the public interest must consider how individuals will actually behave. Most people are not guided by the public interest in their everyday behavior, and they are unlikely to understand how to promote it—hence the need for mechanisms of social coordination.

Many public choice theorists believe that markets generally offer the most efficient mechanisms for promoting social welfare. However, aside from the most hardcore libertarians, most people believe that some regulations are necessary to prevent, if not market failures, at least antisocial and rights-violating behavior, or to deliver certain goods and services. Markets can’t solve crime, and even most economists agree they cannot satisfactorily provide public goods such as national defense, streetlights, or clean air. Public goods are available to all, such that normal market competition fails to price them adequately. Usually, they need to be supported collectively through taxation. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to ask who stands to benefit from certain rules, for not all rules serve the public interest. This approach can illuminate ostensibly innocuous or even beneficial policies that, upon closer examination, prove to be misguided. It may sound cynical, but cynical behavior requires a cynical analysis.

I aim to apply this framework to current debates about AI tools, specifically large language models and image generators, in academic research. The leading journal Ethics recently implemented a new AI policy clarifying the scope of legitimate AI use in authoring submissions. The journal’s editors should be commended for attempting to address a genuine problem: the misuse, overuse, and abuse of AI tools in academic research. AI-restrictive policies seem reasonable in a rapidly evolving context. Many journals are inundated with fully AI-generated submissions and reviews, many of which may violate intellectual property, privacy, and established norms of academic integrity. Clearly, some new policies are required. But before examining the policy closely, a few words about public choice.

What is Public Choice?

Public choice theory is a research program or framework developed by economists and political scientists, including Kenneth Arrow (of Impossibility Theorem fame), James Buchanan, Gordon Tullock, and Mancur Olson. In The Logic of Collective Action, Olson explained how small, organized interest groups can successfully lobby for “wrong-headed” rules that benefit them at the expense of a large, unorganized group (like the general public).

Public choice applies economic analysis to the study of political behavior. Rather than assuming politicians, bureaucrats, and voters act as selfless public servants pursuing some abstract public interest, public choice treats them as rational (if partially ignorant) actors pursuing their own interests within political institutions. The theory doesn’t treat people as purely selfish; instead, it posits that they respond predictably to incentives, and that institutional design must account for this reality.

Public choice sheds light on how regulations actually operate, as opposed to how their proponents claim they do. Understanding these principles helps us see patterns across seemingly disparate policy domains—from occupational licensing to zoning laws to, as I’ll argue, academic publishing policies.

The following principles of public choice will be important:

Concentrated benefits, dispersed costs: Special interest groups succeed because they reap concentrated benefits from policies while costs are spread thinly across many people. Farmers lobby intensely for subsidies that cost each taxpayer a few dollars but save the industry millions of dollars. The industry organizes and mobilizes; individual taxpayers barely notice.

Regulatory capture occurs when interest groups directly or indirectly control a regulatory apparatus, resulting in regulations (or the lack thereof) that tend to serve the interests of incumbents rather than consumers or the public. This is true at the legislative and agency regulatory levels, as well as within professions. Government officials may attempt to prioritize their own interests over the public interest. Medical licensing boards staffed by physicians restrict entry to the profession in ways that protect existing practitioners’ incomes more than they protect patient safety.

Rent-seeking: Individuals and groups compete for government or institutional favors that protect them from normal market competition. Rather than creating value through productive activity, rent-seekers expend resources to secure special privileges—such as occupational licenses, protective regulations, subsidies, and favorable tax treatment—that enable them to extract value from others while creating significant social inefficiencies. According to “Tullock’s Paradox,” rent-seekers will spend resources to pursue special privileges at a lower cost than the value of the privilege to them.

Deadweight loss: Regulations that prevent mutually beneficial transactions create deadweight loss—the loss of economic efficiency when equilibrium is not achieved. Price controls, red tape, or licensing requirements can reduce innovation, ultimately increase prices, and prevent interested agents from completing transactions that would have made everyone better off.

While most people act in ways they believe promote the public interest, public choice teaches us that we cannot ignore the rational self-interest of those shaping the rules. How could this apply to academic publishing? When examining a new AI policy, we must ask whether these restrictions are primarily intended to safeguard the public good of knowledge or scholarly integrity, or whether they serve as a barrier to entry. Where a policy forces researchers to spend their efforts avoiding efficient AI tools just to satisfy a legacy gatekeeping model, Tullock would predict stagnation—resources are wasted on unproductive activity. The cynical (or public choice) interpretation is that policies can result from rent-seeking activity (protecting the status and scarcity of human-only labor).

When applying this framework to academic publishing, we can distinguish between two distinct types of goods. Knowledge itself is a public good—it’s non-excludable (once published, ideas spread beyond any paywall) and non-rivalrous (my reading Rawls doesn’t prevent you from reading Rawls). However, publication in a top-tier journal like Ethics is also a positional good; it is highly rivalrous and strictly excludable. Public choice theory suggests that while a journal’s stated mission is to facilitate the intellectual public good, the actors within that system—editors, reviewers, and authors—have a rational incentive to protect the scarcity and “rent” of their positional status. When we examine AI-restrictive policies, we are looking for this friction: does the policy prioritize the efficient production of knowledge, or does it serve as a barrier to entry that protects the value of traditional human capital?

What About Journals?

So cui bono? Who stands to benefit from AI-restrictive policies? Potential candidates include readers, authors, editors, academic institutions (for hiring, tenure, and promotion purposes), and the broader public—including taxpayers who fund much academic research through grants and public universities.

In economic terms, published philosophical work functions largely as a public good. This creates the classic public goods problem: markets tend to under-provide such goods because individual actors can’t fully capture the value they create. Hence, we need (in part) public funding of research and universities. However, while knowledge is a public good, journal prestige is an excludable positional good that publishers and/or editors may be trying to protect through AI restrictions.

If journals exist to provide the public good of philosophical understanding, we can ask: What institutional arrangements best serve that goal? Just because markets under-provide public goods doesn’t mean guild-like regulation will be optimal. Public choice says: the people tasked with providing public goods also respond to incentives, and those incentives may conflict with maximizing social welfare. When AI threatens to dramatically reduce the cost of producing philosophical research, scholars have concentrated interests in delegitimizing AI assistance to preserve their funding stream—from grants to salaries—while taxpayers and students bear the dispersed costs of supporting potentially less efficient research.1

In the last couple of years, major publishers and many academic journals have adopted policies surrounding AI use for research, writing, editing, and reviewing. Today, I just want to focus on Ethics.

The Ethics Policy

As noted, the new Ethics policy, while flawed in my view, addresses a real problem. Other journals may experiment with different policies. Let a thousand flowers bloom as we figure it out—the same goes for AI policies in our syllabi; I know I’m revising mine every term. Also to their credit, the editors of Ethics are doing a thankless job and publishing some of the best work in ethics, as well as in legal, political, and social philosophy. It’s a premier journal. It will publish some duds, but you’re practically guaranteed to find cutting-edge philosophy, on top of hundreds of classics, in its pages.

Now on to the policy. As the Ethics website now states, “things are moving so fast that the editors have no hope of anticipating all relevant changes to both the AI tools themselves and the professional norms and practices governing their use. We would, nevertheless, be remiss if we didn’t provide some guidance.” The principles that contributors are expected to comply with are the following (emphasis in bold is mine):

AI tools cannot author or even co-author a submission. Authors and co-authors must take full moral and legal responsibility for their submissions; they must take responsibility for the assertions that they make, the arguments that they proffer, and the sources that they cite or fail to cite. Since AI tools cannot take responsibility, Ethics will not consider submissions that have been authored or co-authored by an AI.

Authors must never take credit for work that’s not their own. Taking sentences of text from a generative AI tool and presenting them as your own words is plagiarism—at least, insofar as we take plagiarism to be a form of intellectual dishonesty in which one takes credit for work that’s not one’s own. Using generative AI to come up with a list of objections to a thesis or argument and presenting them as your own is also plagiarism. Consequently, authors who use text, images, or other content generated by an AI in their submission must be transparent about this, disclosing which tools were used and how. In cases where an original human source cannot be identified, authors should, then, include something like the following note: “I first became aware of this objection through the use of ChatGPT, OpenAI, April 16, 2025, https://chat.openai.com/chat.”

It’s important not only that authors avoid taking credit for work that is not their own but also that they give credit where credit is due. The problem with merely citing an AI tool—say, as the source of an example or objection—is that the AI tool may not be the original source. The original source may instead be an author whose work was used to train that AI tool. Thus, attributing some example or objection to ChatGPT could be just as problematic as attributing an objection to your colleague when all they did was tell you about some objection that Rawls raised. Thus, authors may need to track down the original source of an example or objection generated by an AI tool and cite it.

The editors of Ethics value human creativity; we, therefore, value work that presents the author’s own original ideas and insights more than work that presents ideas and insights that don’t originate with the author. For this reason, content that does not originate with the author may be deemed less desirable and publishable—at least, other things being equal.

Let’s unpack this.

Authors must disclose “which tools were used and how.” This sounds like simple transparency. But required disclosure is to be paired with the assumption that “content that does not originate with the author may be deemed less desirable and publishable.” Even if your AI-assisted work is excellent—even if it advances understanding more than purely human work—it arrives marked as suspect, “less desirable,” by virtue of its provenance.

Compare this to how we treat other tools. Philosophers typically don’t disclose their use of reference management software, university library databases, Google Scholar, PhilPapers, and many casual conversations with colleagues, let alone students, may go unmentioned. These tools are unmarked and presumed to be legitimate. The disclosure requirement for AI singles it out as requiring special justification. This asymmetry suggests that the policy regulates production methods, not content.

The policy imposes a hefty burden: “authors may need to track down the original source of an example or objection generated by an AI tool and cite it.” The rationale: AI tools draw on training data, so citing ChatGPT is akin to citing your colleague when the actual source is Rawls. This requirement sounds principled, but it becomes absurd in practice. First, it creates a massive transaction cost, losing much of the efficiency gains afforded by AI. Furthermore, AI systems are trained on ungodly amounts of text. When ChatGPT generates an objection, there may be no single “original source”—the objection might recombine, in a truly novel way, elements from dozens of disparate works. Demanding that authors track down sources that may not exist, or that would require examining the AI’s entire training corpus, makes substantial AI use effectively impossible. When a colleague mentions an objection, we can ask, “Where did you encounter that?” and trace it back to its source. AI systems don’t work that way—they’re statistical models that generate text based on patterns in training data, not retrieval systems that copy specific sources. Web-based research mode may rely on specific sources, but it typically reveals its sources. In this respect, it is more akin to an article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (caveat: for now, the latter remains incomparably better and more reliable). In sum, demanding traditional attribution for AI-generated content either imposes a framework that reveals a misunderstanding of the technology or treats it unjustifiably as being different in kind from traditional research tools.

The policy illustrates the “indirect damage” Tullock feared. From a public choice perspective, the requirement to systematically track down the sources of every AI-generated objection creates an artificial barrier to entry and functions as a tax on efficiency in the name of integrity. By mandating that AI-assisted researchers perform redundant manual labor, the journal protects the competitive advantage of scholars who either can access their own external repository of knowledge (e.g., research assistants) or do not want to be placed at a competitive disadvantage because they lack the skills to use AI. The policy effectively “rents” the prestige of the journal only to those willing to pay the price of inefficient, legacy research methods.

The policy states “AI tools cannot author or co-author a submission” because they cannot “take full moral and legal responsibility.” If authorship is fundamentally about taking responsibility for claims, then yes, only humans qualify. But if journals exist to publish the best philosophical work—the most truth-conducive, the most insightful, the most technically sophisticated—then authorship could simply signal provenance, independently of credit. A cynic could say that the principle ensures that reputational capital remains tied exclusively to human actors within the existing prestige hierarchy. But we could have systems where humans take responsibility while acknowledging AI contributions transparently, without devaluing their work. The current policy forecloses this possibility by treating authorship as necessarily tied to academic credit while explicitly stating that work “that does not originate with the author” is “less desirable and publishable” regardless of its quality.

This reveals a guild-like logic. The policy protects a system in which research must be produced through traditional human cognitive labor to be considered valuable. It prioritizes process over outcomes, valuing the preservation of traditional skills over the advancement of understanding. And it does so under the banner of responsibility and academic integrity—just as doctors invoke patient safety when restricting nurse practitioners from performing procedures they’re competent to handle.

What is the central mission of a journal? To publish the best philosophical output, measured by truth, understanding, or originality? To maintain conversation between authors, critics, and readers? To act as credentialing institutions doling out academic credit usable as currency for jobs, grants, merit raises, tenure, and promotion? All of the above?

If we take seriously the first possibility—that journals should publish the best work by standards of truth, understanding, or originality—then we must ask: What if AI assistance could produce better philosophy?2 Not by replacing but by enhancing human thinking, by helping articulate arguments more clearly, exploring new ideas, identifying relevant literature more comprehensively, spotting logical gaps, or exploring conceptual space more systematically. If journals are in the business of publishing the best and most important work, they should be mostly indifferent to how that work was produced, provided it meets their substantive standards and commits no fraud or academic dishonesty. And even if we value human conversation, as I do, why should journals necessarily host it? Why should they restrict themselves to such conversation? And why would conversation itself—independently of its output—be publicly supported, when many other equally valuable activities are not?

The Public Choice Analysis

Deadweight Loss, Rent-Seeking, and Other Terrible Things

The policies professional journals adopt determine the payoff structure of choices authors can make. Assume some AI tools can significantly improve a manuscript or lead to genuine insights that (1) would not otherwise be possible and (2) satisfy assessment criteria for quality or importance. Authors who care about delivering the best work and having it published in leading journals may think using such tools warrants it, simply because their ends are better served this way. If journals are homes for the best or most important work, we should worry if journals bar publication of such work.

Restrictive policies could lead journals to publish suboptimal work.3 Because authors respond to incentives, not just a desire for truth or understanding, some will refrain from using AI tools and miss out on ways to make their work better. A graduate student who could use AI to help structure a complex argument, identify connections across literatures they haven’t fully mastered, or draw finer distinctions might produce superior work. But if journal policies stigmatize AI use or require extensive disclosures that editors view suspiciously, authors face strong incentives to forgo the tools, producing work that’s demonstrably their own but suboptimal relative to what they could have produced.

It may be better for students’ training not to use generative AI tools, but the role of journals is not to police graduate students’ training. Schools can enforce their own policies. If an author’s status should not be revealed to editors and reviewers, such considerations should remain irrelevant to the assessment of a submission.

Because similar incentives are widely shared and authors compete in the credit economy (for jobs, publications, grants), AI policies shape individual and collective behavior. With AI-restrictive policies, we may end up with a large body of suboptimal work. Most published work will still be excellent—there’s no shortage of brilliant work in philosophy journals. But why think we’ve reached a ceiling? By widely adopting overly restrictive policies, the profession may collectively produce less truth, less understanding than it could.

Restrictive AI policies, enacted within a specific institutional apparatus, are likely to serve some interests. But it’s not obvious that in the current and (more importantly) future AI landscape, the interests served align with what philosophers claim to care about: truth and understanding. Even if we believe that human dialogue and conversation are intrinsically valuable aspects of the philosophical enterprise (as I do), they are not our only goals. We also care about truth and understanding. Nor should we claim these ends necessarily require the dialogical part. It shouldn’t be too hard to imagine philosophical outputs that stand on their own terms and help us see the world anew or solve problems long thought intractable (say, on consciousness or in population ethics). Just because we’ve been accustomed to philosophical insights being produced by conversing human beings doesn’t mean it’s the only way. If we grant that even marginally better philosophical insights could be produced by AI, in ways either non-substitutable or very inefficient without AI assistance, AI-restrictive policies will create deadweight loss.

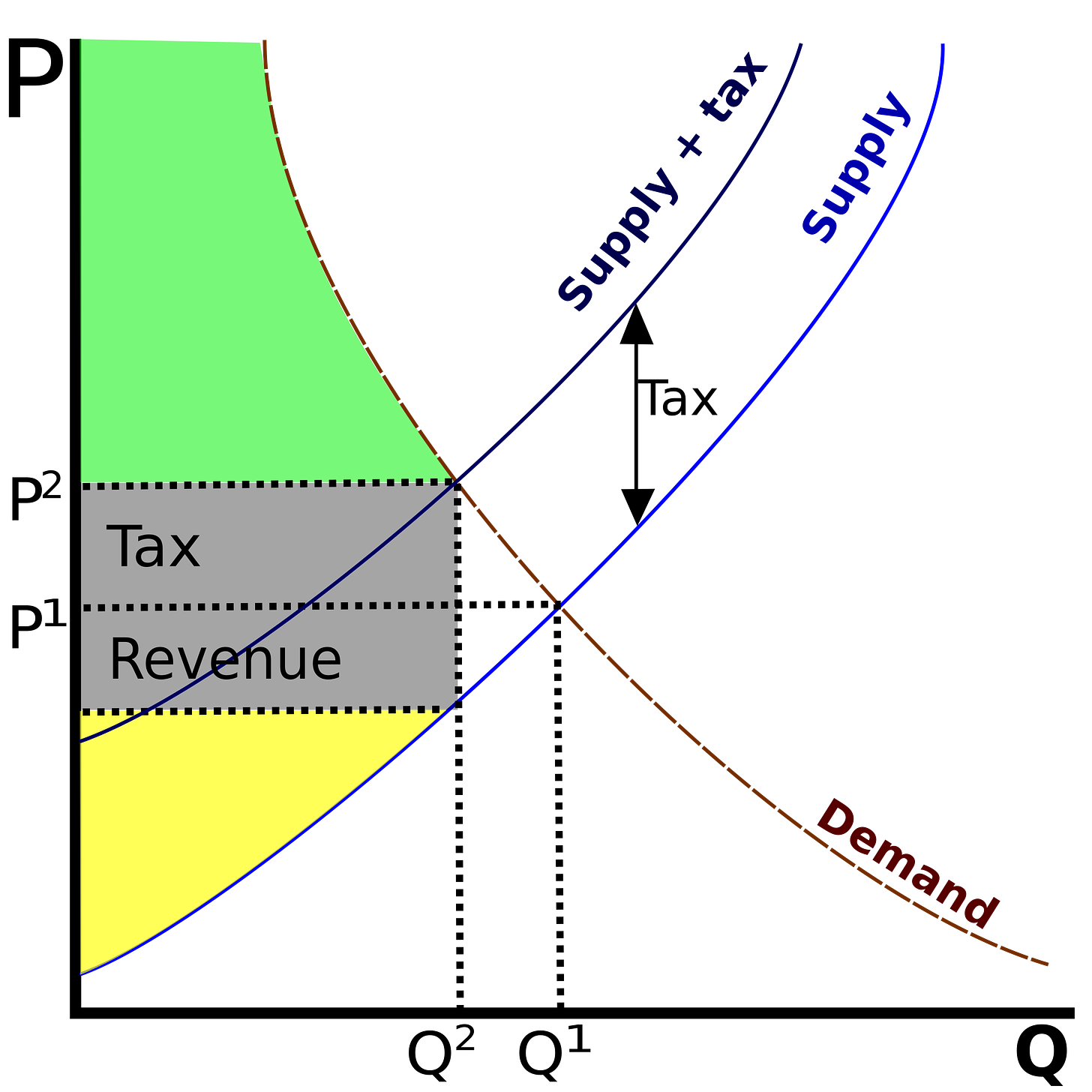

We can visualize it through a standard supply-and-demand model. When a journal imposes high-friction AI rules (the “tax”), it effectively shifts the supply curve of research upward by imposing a kind of regulatory tax on efficiency. The resulting loss (represented by the small triangle under the demand curve) is the cost society incurs for protecting traditional scholarship over the efficient production of knowledge. Here is a standard graph illustrating the concept:

Other principles also apply to the discussion:

Concentrated benefits, dispersed costs: Established philosophers benefit from policies that privilege traditional methods. They preserve the value of skills they’ve spent careers developing, as well as the funding model that supports their careers. Meanwhile, costs are dispersed across readers who miss out on potentially superior work and junior scholars and non-native speakers who might leverage AI to compensate for their disadvantages.

Regulatory capture: Academic journals function as both producers and regulators of philosophical work. The people writing AI policies—editors, editorial board members, established scholars—are the same people whose human capital and professional status might be threatened by AI.

Rent-seeking: Restrictive AI policies allow established scholars to use institutional power to preserve the value of their traditional skills by restricting access to tools that might optimize philosophical production.

In sum, by enforcing high-friction AI rules, journal editors are not protecting the public’s access to knowledge, but rather the scarcity of the journal’s stamp of approval. Public choice theory reveals that the “rent” here is the maintenance of a high-effort barrier, which ensures that only those with traditional, high-cost human capital can compete. As Tullock would argue, when we prioritize the protection of this status-rent over the efficient production of knowledge, we intentionally choose stagnation over progress.

The Guild

Standard objections to AI use concern authenticity, academic integrity, or proper attribution of credit. These concerns are legitimate, much like “protecting consumers from unqualified practitioners” sounds legitimate when doctors advocate restrictive licensing. We can think of professions implementing internal policies as guilds. Think of doctors and lawyers imposing lengthy training requirements and restricting who can perform routine services—requirements going far beyond what’s needed to ensure basic competency. Or the hotel industry opposing Airbnb, cab drivers opposing rideshare services like Uber or Lyft, or self-driving taxis like Waymo. Or real estate agents lobbying for laws preventing homeowners from easily selling properties without their services. What we have are special interest groups lobbying for regulations—capture—under the guise of quality control, consumer protection, or public safety, while primarily serving their own interests and depriving customers of valuable services or lower costs by restricting supply.

Whatever you think of Waymo vs. regular taxis or Airbnb vs. traditional hotels, or cheaper, qualified foreign-trained lawyers vs. guild-approved lawyers or doctors, many people value those services but don’t use them because they’re outlawed, unavailable, or too expensive. A scheme of social coordination whose principal effect is to raise prices (for consumers) and barriers to entry (for graduates and job seekers) cannot be socially optimal. Especially when we ask whose interests it serves, and the answer is obviously the very interest group that actively lobbied for those special regulations.

The pattern is consistent: established practitioners use quality concerns as a pretext for restrictions primarily serving their economic interests. Crucially, such rent-seeking restrictions create both deadweight losses (services that would have benefited both parties don’t occur) and opportunity costs (talented individuals who could have contributed are excluded).

Now, let me draw an imperfect analogy with the corners of our profession in charge of regulating the credit economy. By “credit economy,” I mean the system where academic publications (alongside citations, awards, and other units of prestige) function as currency that scholars accumulate and exchange for professional advancement. Publications, especially in prestigious journals, are “credits” that can be spent on jobs, tenure, promotions, grants, and salary increases. Authors compete to accumulate credits, while journals act as gatekeepers controlling the supply of credits. In this framework, publications are not just about disseminating ideas but also about professional capital in a competitive system.

You may be part of that guild. I am—I write, present, submit, and referee papers. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with being part of a guild. But merely by being part of a guild, you have some special interests that may not perfectly align with the interests of those outside the guild.

Most guild members are individuals whose human capital is invested in skills such as close reading, analysis of complex ideas, rigorous argumentation, and the patient craft of polished writing. These skills serve valuable epistemic ends, but they can also be bound up with our self-conceptions as philosophers. Because for many, this self-conception precludes the use of crutches and values authenticity and autonomy, it tends to respond negatively to a different way of playing the game. Some of us have a vested interest in preserving a system that values those skills to the exclusion of crutches, even if the crutches could help produce better philosophy. But if we agree that philosophy is not just a game (where crutches are cheating), if it seeks goods beyond its own practice, then the guild’s reluctance to embrace crutches may be questioned.

Most journal editors care deeply about philosophy. However, if journals serve as providers of a public good—advancing philosophical understanding—then their policies should maximize that good. The question is whether restrictive AI policies serve that goal or protect guild interests at the expense of better scholarship. Public choice theory predicts that even well-intentioned actors will adopt policies serving their interests when institutional incentives are misaligned with their stated mission. These guild members may not be consciously protecting their turf. You may genuinely care about academic integrity, the value of human creativity, or the harms caused by AI companies. You may even think AI compromises the quality of philosophical work—though if that’s the case, we don’t need a policy; bad work will be weeded out through regular refereeing. But you may also fear being displaced by AI. You respond to incentives. We all do.

Another Source of Anxiety

There is a different framing of roughly the same problem that was suggested to me by Dustin Crummett. Funding for research, from grants to salaries, depends on convincing taxpayers, students, and private organizations that funding human research is sufficiently valuable. If AI could produce comparable research much more efficiently, this entire funding stream would be threatened. The government owes taxpayers, and universities owe students, a good reason for subsidizing inefficient researchers. The primary reason for subsidizing research should be the pursuit of truth, understanding, and contributions to social welfare—not the preservation of a particular worthwhile mode of production. Scholars understandably worry about their livelihoods (I do); therefore, they have an incentive to delegitimize AI-assisted work.

The Other Side of Cui Bono

Public choice analysis cuts both ways. If we should be skeptical when journal editors claim restrictive AI policies protect philosophical integrity, we should be equally skeptical when AI companies claim permissive policies advance knowledge.

OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and other AI companies have a vested interest in the widespread adoption of their tools. They benefit directly from normalizing AI use in academia: every philosopher who relies on ChatGPT or Claude is a potential subscriber, and every published paper acknowledging AI assistance is free advertising. The companies’ rhetoric about “democratizing access to knowledge” or “accelerating scientific discovery” may be sincere, but it’s also excellent marketing.

Moreover, AI companies face incentives that may conflict with the public interest. They benefit from creating dependency on their tools, even if that dependency erodes scholars’ traditional skills: I may produce better writing while becoming a worse writer. They profit from academics uploading manuscripts and research ideas into their systems, providing valuable training data, regardless of intellectual property implications (unless one runs the model locally or trusts models like Claude’s opt-out feature). They gain from shifting academic work toward tasks AI handles well (broad research, prose generation) and away from tasks it handles poorly (genuine innovation, accurate citations), even if this shift doesn’t optimize for good philosophy.

There are other legitimate concerns that restrictive policies attempt to address, besides privacy, intellectual property, and skill erosion—such as labor displacement, future energy use, and concentration of power. Moreover, if publishing requires access to the best AI tools, and those tools are expensive or proprietary, we shift the barrier to entry rather than eliminating it. The guild’s concerns about integrity, authenticity, and human creativity reflect genuine anxieties about what might get lost. The problem is that guild-like structures create institutional incentives to weight these concerns heavily while discounting potential benefits, just as AI companies have incentives to do the reverse.

Conclusion

Public choice theory doesn’t tell us that guilds are bad and markets good, or that regulation always serves special interests. It tells us people respond to incentives, and we should design institutions that align those incentives with our goals.

If our goal is to advance philosophy, we must ask: What institutional arrangements best serve this goal? This is harder than “Whose motives are purer?” or “Who should we trust?” Neither journal editors nor AI company executives are disinterested parties. Both have mixed motives—genuine concern for their stated mission combined with responses to incentives.

The question is whether restrictive AI policies actually protect the values journals claim to serve, or whether they protect guild-like interests at the expense of philosophical progress. And whether permissive policies actually advance knowledge, or advance corporate interests at the expense of scholarly integrity.

My central—perhaps overly cynical—claim has been that current restrictive policies are suboptimal, but that doesn’t mean unconditional permission is optimal either. We need policies that:

Allow scholars to use AI when it genuinely improves their work

Require genuine transparency about AI use without stigmatizing it

Evaluate work primarily on its contribution to understanding, not its production method

Our admittedly tentative approach fails these criteria because editors’ institutional position creates incentives to over-weight production constraints. Recognizing this doesn’t mean embracing whatever serves the interests of AI companies, but thinking carefully about what institutional design would actually serve philosophy.

Disclosure: I used Claude Sonnet 4.5 (claude.ai/chat) and Gemini 3 (gemini.google.com/app) to gather information about AI policies across publishers, spell out an analysis of guild behavior in Public Choice, generate some examples, solicit input on language and organization, and proofread multiple drafts for spelling, grammar, clarity, and consistency. I also used Wikipedia, a laptop computer, a word processor, Grammarly, caffeine, remote memories, and feedback from Dustin Crummett.

Thanks to Dustin Crummett for this point.

I’m not saying it does or that it necessarily will. But it could and probably will. When will AI be able to produce, with basic instructions but minimal intervention, a paper worthy of publication in Noûs? I don’t know, but I predict it will be during my lifetime. Relax the parameters, allowing more direct human collaboration in the process, and it’s just a matter of a few years.

I bracket scientific discovery here because it raises slightly different questions, although I think it would strengthen the case for relaxing restrictions even further. The stakes may be low when it comes to philosophy, but we could imagine life-saving scientific breakthroughs being slowed down due to AI-restrictive policies.

Thank you for the piece. There is a concern, it seems to me, that your argument is too reliant on a rather controversial position within epistemology, namely, that philosophy can (much less that its primary goal is to) generate "truth" or at least true beliefs. But if Quine (inter alia) is to be believed, the domain of a priori truth is illusory; or at least, we should be wary of claims to have arrived at a priori truth without a defense of the position that can found at all. There are two alternatives: 1) the "cash value" of philosophy is the inculcation of true beliefs in some minimalist sense (this construal seems most apt in the case of ethics/pol. phil) or 2) the central virtue of philosophy is, as I believe, its intrinsic intellectual value to its practitioners. You develop a position along the lines of 1) when you reference the "social welfare" benefits of high-quality philosophy. But this claim is dubious. 21st Century Analytic philosophy is notoriously abstruse and rarefied, as has been belabored and bemoaned by both proponents and detractors. Who is to benefit from the production of AI-augmented "cutting-edge" philosophy save those few savants already fluent in the terms of the relevant debate? The value must therefore be to practitioners of philosophy. But if they are incentivized to offload cognitive (and constitutively philosophical) tasks to AI, then it seems that, at least to a certain degree, the intrinsic value of the philosophical practice is degraded. If baseball players all wore vision enhancing goggles at bat, it would still be baseball they played, but one constitutively valuable skill (hand-eye coordination) would be rendered obsolete. The game would lose some of its intrinsic worth. In the case of philosophy, moreover, we should note that practitioners already function as sole producer as well as primary (perhaps sole) consumer of research. But should their ability to understand that research erode, for the cultivation of their skills are to be subordinated to the noble pursuit of pure knowledge, and indeed the rigor of AI may exceed their diminished or at least inferior cognitive faculties - then the already comically parochial audience of philosophical research will sustain a further diminution. At least, I think your argument that "The primary reason for subsidizing research should be the pursuit of truth, understanding, and contributions to social welfare" requires a further defense of why these reasons are preeminent and an articulation in more detail of how our embrace of AI can promote them.

Interesting! Help me understand: how can a claim 'be too cynical to be true'? :) I'm not just trying to nitpick, but it seems to me that cynicism is just orthogonal to the truth (but not to reputation management -- get out of my head, Dan Williams!).