Life is weird. So is time. So is the wide range of animal lifespans and life histories (when they mature, reproduce, age, morph, and die).

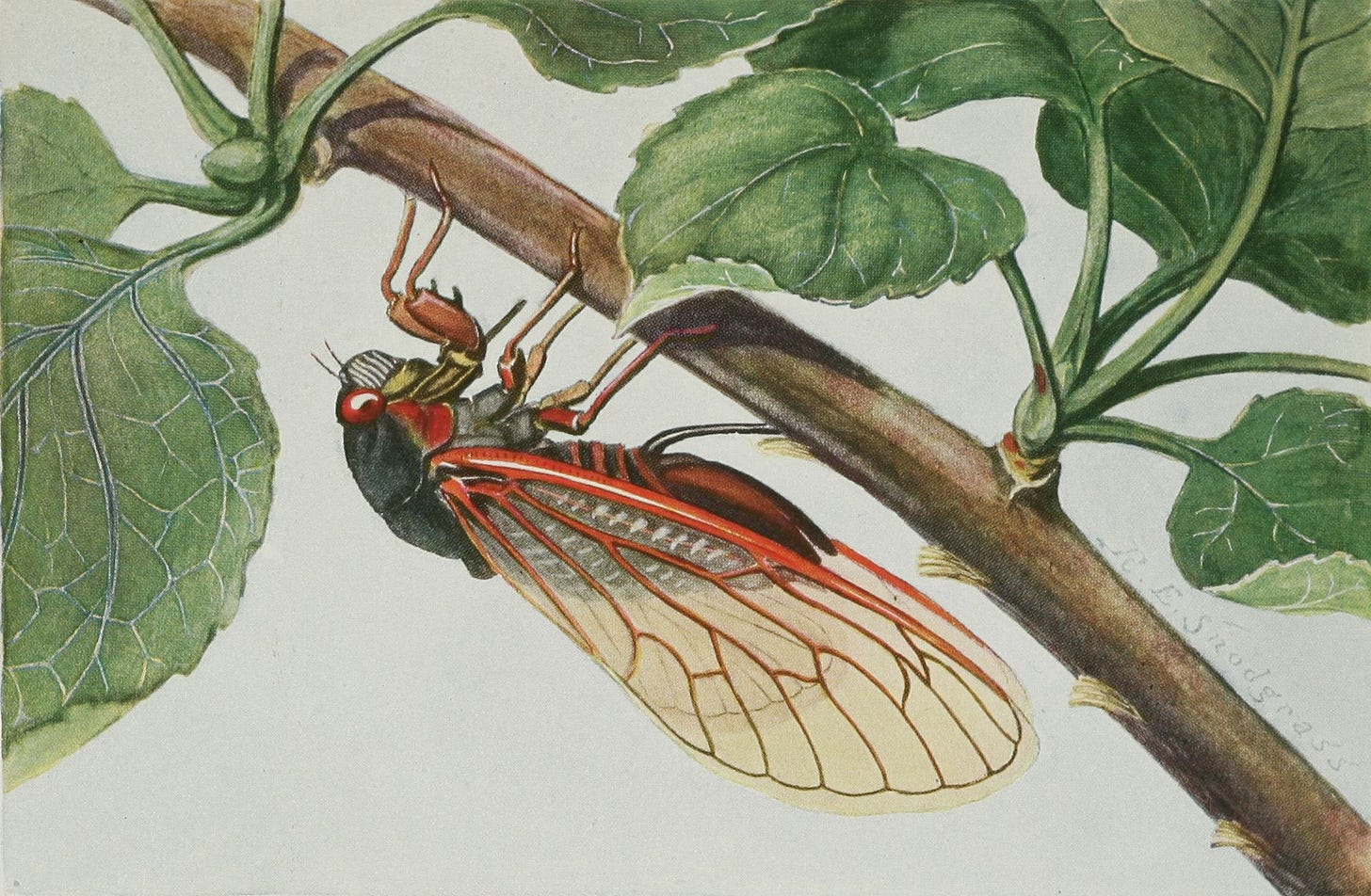

Right now in parts of the U.S. Midwest and Southeast, two broods of periodical cicadas are emerging (there are seven such North American species in the genus Magicicada). Periodical cicadas are a small minority of the thousands of documented species, nearly all of which are annual cicadas. Loud bugs? What’s remarkable about that?

Well, for starters these are exceptionally large broods—known as XIII and XIX—numbered in billions. Slightly confusingly, they are rising above ground for the first time in 17 and 13 years, respectively. Because of their precise cycles, the last time these two broods co-emerged was in 1803.

After spending their juvenile years developing underground, they emerge in sync to transform into adults, mate, and lay eggs. The distinctive buzzing drone of the cicada chorus is produced by large groups of males, each singing a mating song to attract females. (Wild Animal Initiative)

Two things are puzzling about these insects. Why do they spend so much time underground? And why is the emergence of a brood synchronous? The synchronicity of the current co-emergence of the two broods is not puzzling, it follows mathematically from the within-brood synchronicity (though for good measure, evolution threw a wrench in that regularity with also occasional four-year jumps in development that result in switches between 13- and 17-year cycles). The most common hypothesis is that these two puzzling facts minimize predation risk—reduced availability to predators selects against predators that may have evolved to depend on them and large-scale emergence compensates for whatever predation does happen simply by offering more than predators can chew (satiation).1 However, it remains puzzling to me why, if the strategy pays off, it is so unusual among cicadas. Annual cicadas have not gone extinct despite making themselves regularly available, in more digestible numbers, to potential predators.

Periodical cicadas spend 99.5% of their unusually long lives underground, enjoying an abundance of food and a relative lack of predators. It’s likely that predation becomes a serious threat only in the final few weeks of their lives, when they emerge and become adults. (Wild Animal Initiative)

Not much is known about their life underground for all these years. But imagine: most of their life is spent underground in a nymphal stage feeding on plant root xylem fluids. They actually enjoy long lives by insect standards (even accounting for metamorphosis), though we don’t know what sorts of experience nymphs are capable of and how unified the lives of animals that undergo metamorphosis are. After emerging, they live for about three to six weeks, most of which is spent singing for males (mating calls), mating, and laying eggs for females. Way to make your entrance into the upper world and leave!

This doesn’t mean their limited existence above ground consists of a simple sing- mate-and-die sequence.

Magicicada males gather and sing in chorusing trees in large groups. Species in this genus have unusually complex courtship sequences, involving multiple species-specific songs and tactile behaviors. Males engage in call–fly behavior, alternating short flights with bouts of calling. As pair formation progresses, males use different mating songs and stop signaling once they begin copulating; copulation lasts for several hours.2

I live in Charleston, SC. Upstate, parts of brood XIX are currently emerging and chirping, resulting in a locals’ varied range of responses from panic (call 9-1-1) to annoyance to awe and wonder. In two recent trips, one upstate and one in Georgia, I unfortunately did not get to hear or see any cicadas. But I take some comfort in the fact that thousands of fellow South Carolinians are wondering about these unique creatures, and perhaps realizing that bugs are not always a nuisance. They are not just bugs, actually. Periodical cicadas are your periodical reminder that there are so many unique ways to live—and die—in this world.

Octopuses have short life spans, especially compared to their remarkably complex behavior and cognition. Most cognitively complex animals live much longer (also more socially) than octopuses. Giant cuttlefish (other marvelous cephalopods) and most octopuses live one or two years. The giant Pacific octopus can live three to five years. “I could hardly believe it”, writes philosopher and diver extraordinaire Peter Godfrey-Smith in one of my favorite books, Other Minds.3

I had assumed that the cuttlefish I’d been interacting with were old, had met humans often and worked out how they behaved, and had seen many seasons pass in their patch of ocean. I had assumed this partly because they seemed old; they had a worldly look. They also seemed too big to be so young, as they were often two or three feet long. I realized that year, though, that I’d come across these cuttlefish in the early part of the breeding season, and all the animals I’d been visiting would soon be dead. (p. 159)

Oh yeah, almost all octopuses start senescence and die shortly after mating (males) or after their brood of eggs hatches (females) (cuttlefish have multiple matings and broods, but only one breeding season).4 Nice.

This reproductive strategy, reproducing once and then dying, is called semelparity. It is quite common in invertebrates, especially insects, spiders, and mollusks (including many species of cephalopods). It is extremely rare in vertebrates, especially land-dwelling vertebrates. The only exceptions are antechinus (a genus of small marsupials, the only documented mammalian exception), some Hyla frogs, and some lizards.5

This strategy is a reflection of the probably universal and inextricable link, and associated tradeoffs, between sex and death. Where competition for mates is highest, the best strategy may be for males to “die trying than not try at all.” Or “sexing-to-death,” as the zoologist and author Jules Howard puts it.6 Howard writes,

Death really is a contract, and animals have evolved to exploit its loopholes in the way that best suits them and the spreading of their genes. On the whole, though, you either throw down your hands and bet big, or bet small and hope to visit some other tables. Either way the house will always win in the end.7

The contract may not be quite as universal and inescapable as we think. Maybe there is a cure for ageing. And there are (in principle) biologically immortal organisms as well as animals whose ageing is very limited (and longevity equally remarkable, albeit not infinite). Still, these are exceptions that prove the rule: their existence presupposes mechanisms to circumvent the ruthless forces that shape nearly all life on earth (and presumably beyond). The comparatively long-lived giant Pacific octopus is also an exception that proves the rule: they tend to reside in depths that make them less vulnerable to predation.

Common in invertebrates doesn’t mean universal—octopuses didn’t have to be semelparous and short-lived. Take crustaceans, about which we’re learning more, slowly realizing “there is more going on inside these animals than has usually been supposed”, writes Godfrey-Smith in one of my other favorite books of all time, Metazoa, his follow-up to Other Minds. In one of several wonderful chapters, Godfrey-Smith follows a one-armed banded shrimp to the end of his life—an individual shrimp, with an individual story, deciphered between the lines. The last section of the chapter is Godfrey-Smith saying goodbye to the shrimp, who is missing both arms, looking “tired, very much on his own, and probably near the end of his days.” (p. 102) As Godfrey-Smith had learned before one of his several encounters with the shrimp, banded shrimps are “long-lived, territorial, and monogamous”. They can live up to five years (in aquaria). They also recognize and tell individual conspecifics apart (p. 100).

Cephalopods stand out because they reproduce like other invertebrates but seem to have mental lives—or behavioral complexity and sensory richness, not just “smarts” (p. 142)—unlike any other vertebrates’ (though, as we’ve seen, crustaceans don’t get nearly enough credit). Godfrey-Smith remarks that most mammals, birds, and fish can live much longer. “Many cephalopods seem both too big and too smart to race through their lives in the way they do.” He characterizes their lives as “experienced compressed.” But this still raises a puzzle: “What is all the brainpower doing if an octopus is dead less than two years after hatching from the egg?”

I will not solve the puzzle, nor does Godfrey-Smith claim to have a definite solution, though he suggests a tentative story, drawing on evolutionary theory. The answer combines two effects, hypothesized by the immunologist Peter Medawar and the biologist George Williams to explain senescence.

Cephalopods’ lifespans are just one extreme version of an evolutionary tradeoff between how long you would like to live and when and how often you mate (to leave as many descendants as possible), given how risky your environment is.

In the abstract, you would like to live and mate forever … But who will leave more descendants, an organism which spends everything on one mating season, or a rival which spends less time now in the hope of reproducing again later? If you spend less now to save something for later, that will do you no good if animals of your kind have little chance of making it to the next breeding season. In that case, it is better to put everything into one mating season, embracing all the options which give you an advantage now, even at the cost of breakdown once the season is done. (p. 172)

Long-lived animals like elephants, parrots, and humans, mature slowly and can reproduce over many years. The longer-lived ones like rockfish and tortoises can go on for even longer. “The lifespans of different animals are set by their risks of death from external causes, by how quickly they can reach reproductive age, and other features of their lifestyle and environment.” (p. 172)

Remember that cephalopods are soft-bodied animals living in a highly unpredictable, predator-filled environment. Shedding their shells in their early evolution was for cephalopods a double-edged sword. It gave their “bodies their outlandish, unbounded possibilities”, which, Godfrey-Smith argued previously in Other Minds, “was crucial to the evolution of their complex nervous systems.” (p. 173) At the same time, the change made them more vulnerable to predators, which itself put further pressure on the evolution of complex, intelligent behavior, including camouflage. But since there’s only so much time they can spend outsmarting their predators—they still have to forage—evolutionary pressures compressed their lifespans.

There is something a bit absurd about octopuses’ expensive investment in such a brief presence on earth. As Schopenhauer, master of the absurd, wrote:8

Directly after copulation, the devil’s laughter is heard.

But you might also think they’re making the most of it. Either way, octopuses are not letting this life happen; they are making it happen, eight arms and myriad colors at a time. Octopuses are agentic.

Big brains, short lives. Life fast, die young.

Many species of tortoises have long life spans, not infrequently longer than most humans—sometimes, as with some giant Galápagos tortoises, much longer than any human has ever lived. A century’s worth of life. Maybe even centuries. Many species take decades to reach reproductive maturity, and then continue reproducing for the rest of their lives—many more decades. Totally different life history.

Octopuses have a fast-paced, short, largely solitary life. Tortoises have a slow-paced, long, largely solitary life.

No one knows what it’s like to be a tortoise or an octopus. These are radically different forms of life, not just because they unfold at different paces and over different timescales than a typical human lifetime. Not just their sensory world, but how tortoises perceive time may be different:

In the case of chelonians like turtles — and their encarapaced brethren, the tortoises — we may know even less about how they experience the world than we do about bats. … [T]heir brains process these visual signals slowly — a quality of certain animal brains that might, some experts have theorized, result in a sped-up perception of time. (In chelonian eyes, do grasses wave frenetically in the breeze and clouds race across the sky?)9

Few even talk about their lives. How many fiction or nonfiction books about individual tortoises or octopuses have been written? My Octopus Teacher, a Netflix documentary, not a book, is the exception that proves the rule. It made an impression that a documentary about a dog could not make. Sy Montgomery is a notable exception. She has written many best-selling books about animals, including The Soul of an Octopus,10 in which we encounter Athena, Octavia, Kali, and Karma (she also just published Secrets of the Octopus with photographer Warren Carlyle.11 And last year, she published Of Time and Turtles.12 But again, these are noteworthy, not expected. We don’t expect the lives of the individual animals to be worth telling, because they’re too alien, short, or boring. Who cares about mollusks or shelled reptiles?

A quick search on Amazon.com reveals a dearth of books about tortoises. Most results are either pet feeding guides or involve some hare-related allegory or metaphor that has little to do with flesh and bones tortoises. There is more about turtles, though not much when you bracket kids’ books, sea turtles, and mutant ninjas. There is of course a lot more about octopuses, especially lately. There are, again, exceptions. See, for instance, the amazing lives of Harriet, Jonathan, Timothy, or Tu’i Malila. Yes, they all have Wikipedia entries of her own; I do not.

But following up on my previous post about mice and rats, is there any principled reason to deny tortoises and octopuses the possibility of meaning? They are agents too, actually fairly interesting ones.

Their lives may seem insignificant, but so do ours. They are no more absurd than human life by dint of being short or slow. Cosmically, any life is insignificant. However, these animals hardly leave their mark on the world. They don’t seem to partake of something greater than themselves. But again, most of us don’t. It’s had to avoid the conclusion that, if their lives are absurd, so are most human lives. Conversely, despite cosmic insignificance, what does give meaning to our lives is within reach for many animals. And if rats can do it, so can octopuses and turtles.

Source: Wikipedia, citing Simon, Chris, Cooley, John R., Karban, Richard, and Sota, Teiji (2022). “Advances in the Evolution and Ecology of Thirteen- and Seventeen-year periodical cicadas”. Annual Review of Entomology. 67: 457–482. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-072121-061108.

Simon et al. (2022), p. 466. References omitted.

Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2016). Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

The one apparent exception is the larger Pacific striped octopus (LPSO), which can reproduce several times over a couple of years.

Howard, Jules (2016). Death on Earth: Adventures in Evolution and Mortality. London and New York: Bloomsbury (p. 115).

Howard, p. 114.

Howard, pp. 115-116.

Schopenhauer, Arthur (1974). “Chapter XIV: Additional Remarks on the Doctrine of the Affirmation and Denial of the Will-to-Live”. Parerga and Paralipomena: Short Philosophical Essays. Vol. 2. Translated by Payne, E. F. J. Oxford: Clarendon Press (p. 316).

Wasik, Bill and Monica Murphy, '“How do we know what animals are really feeling?” The New York Times Magazine, April 23, 2024.

Montgomery, Sy (2015). The Soul of an Octopus: A Surprising Exploration into the World of Consciousness. New York: Atria.

Montgomery, Sy and Warren K. Carlyle (2024). Secrets of the Octopus. Washington, DC: National Geographic.

Montgomery, Sy (2023). Of Time and Turtles: Mending the World, Shell after Shattered Shell. HarperCollins.