For mammals, much of the world, outside of farms, is not seen. Not because it is invisible, but because it is perceived through echolocation. Much of the world, outside of farms, is perceived by bats. Bats are mammals, and a lot of their navigation and foraging is guided by echolocation, which works like this. Bats emit high-frequency sound waves through their mouth or nose, then listen for echoes bouncing back from objects. Their brain processes these acoustic signals, measuring the time between signal emission and echo return, to calculate distance and create a mental map of their surroundings, allowing them to navigate, hunt, and avoid obstacles with remarkable precision. This is basically the technology on which sonars rely. Other species use echolocation as well, especially marine mammals (dolphins, porpoises, and toothed whales).

But I’m exaggerating. Contrary to prejudice, bats are not blind, with eyesight often better than humans in low-light conditions like dawn and dusk. The quality of their vision varies among species: fruit bats have particularly sharp eyesight and large eyes, while smaller insectivorous bats have functional but less acute vision. Echolocation complements rather than replaces vision: vision for general navigation and long-range orientation, echolocation for precision tasks like catching insects. Some species can even see ultraviolet light. Using both systems together are nonetheless able to perceive the world very differently than we, or most other mammals, do—that’s setting aside the fact that many mammals tend to rely on auditory or olfactory perception more than vision.

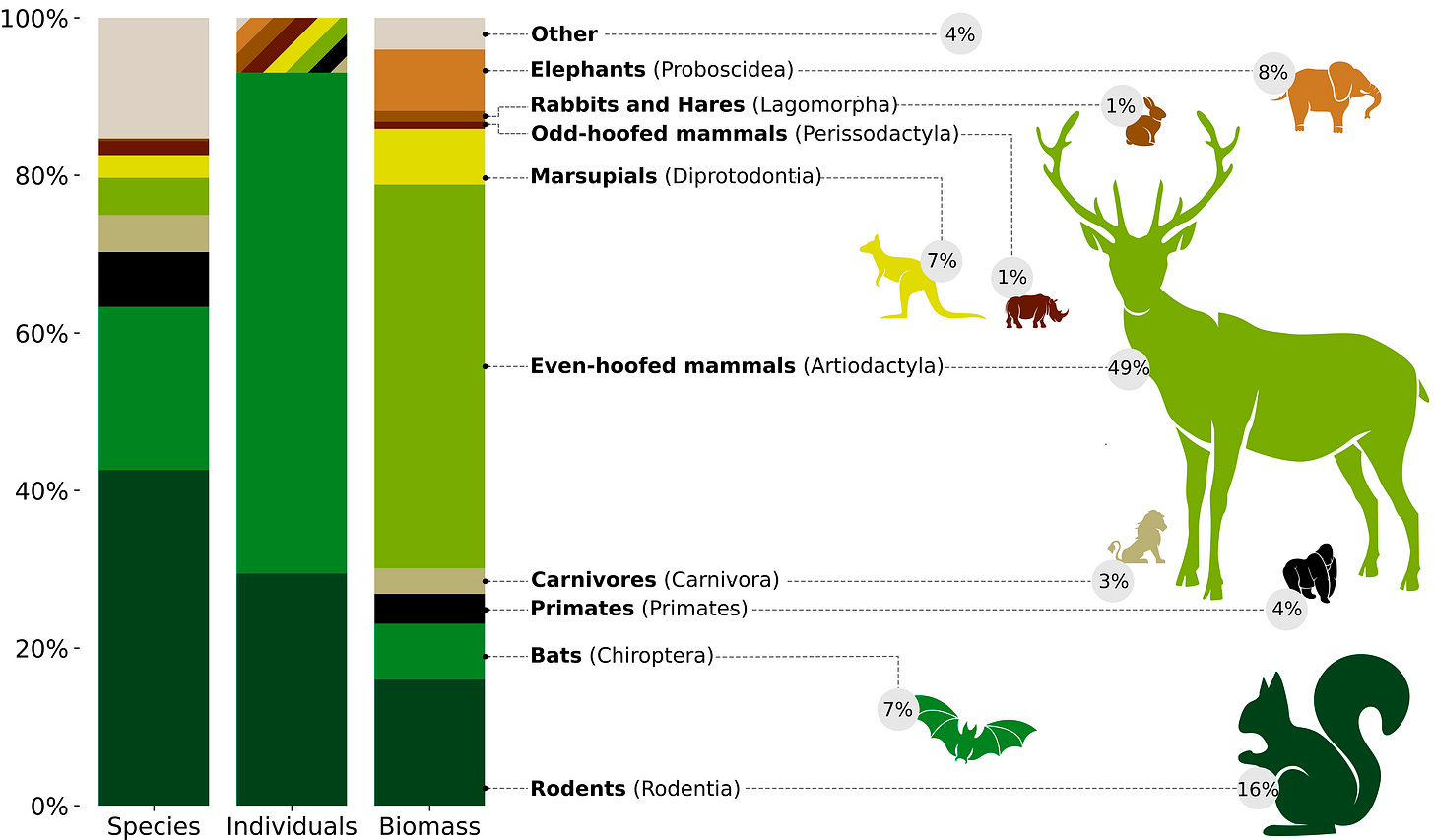

One of the most stupendous facts I have learned in recent years was brought to my attention by one of my favorite philosophers, Peter Godfrey-Smith, in a Twitter thread a couple of years ago. Peter’s comments were based on a recent study of the global biomass of wild mammals in PNAS.1 Peter then included some of the analysis on his latest book, Living on Earth, the last of his marvelous trilogy after Other Minds and Metazoa. According to the study, approximately 7% of this biomass (0.5 million metric tons) is constituted by bats. Not very impressive, but bats are, like rodents, comparatively small and light among mammals. Bats weigh between 2g (Kitti’s hog-nosed bat) and 1.6kg (Indian flying fox and Great flying fox). Bats “comprise one-fifth of species and two-thirds in terms of individual mammals”, as shown in this figure:

That’s right. By a sizeable margin, most individual wild mammals are bats. Admittedly, birds outnumber bats by a factor of 5; fish by a factor of 300 (!).2 Still, numbers-wise, your typical mammal is a bat. The world of mammals is primarily peopled by small rodents and bats.

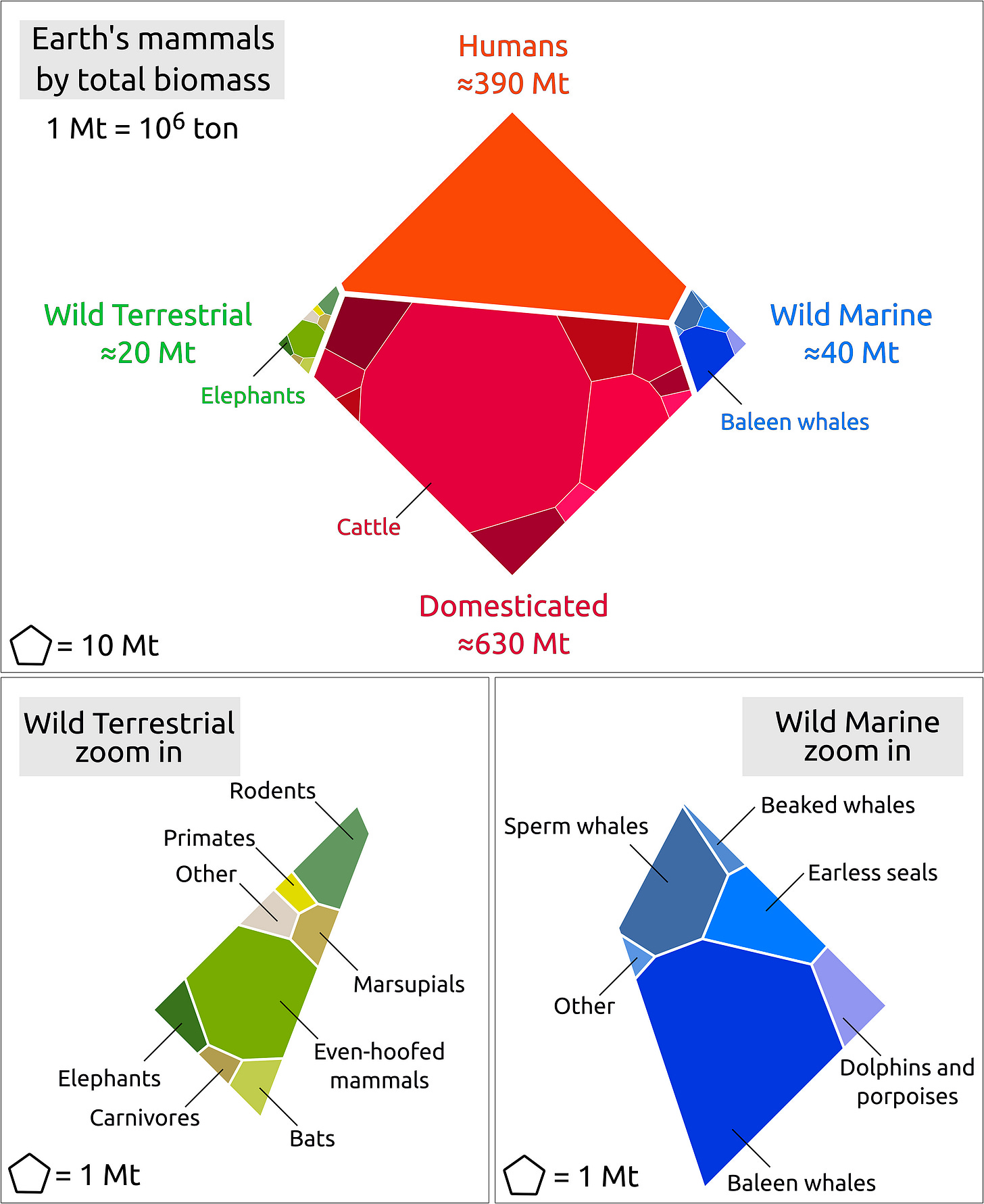

Well, not quite. Wild mammals make up just four percent of the global biomass of mammals on Earth. 62% are livestock and 34% are humans [sources: 1; 2]. Humans and livestock are comparatively large, so this comparison tells us little about the number of individuals. It’s not easy to come by with precise estimates. But estimated “livestock counts”, there are between 4 and 5 billion farmed mammals alive on earth at any given time (higher than the number of animals killed per year, since most of those live more than a year; the reverse is true of chickens3).4

Alright, much of the mammal world at any given time is seen by cows, pigs, goats, sheep, and human beings. But let’s get into the woods and wait for the sun to set, and forget these highly localized and clustered populations of human and nonhuman domesticated animals. Then, most of the world’s mammals are bats. And as we saw, they see but also echolocate. And so, outside of farms, where most mammals live, and urban and suburban areas, where most humans live, darkness is being echolocated. This means that most mammalian experience is either highly constrained (livestock) or radically alien to us (bats). For we have no idea what it’s like to be a bat, at least so argued the philosopher Thomas Nagel in a famous paper.5

In 1974, in “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?”, Nagel attempted a refutation of physicalism, the view that everything, including the mind and consciousness, is physical, though that’s not what concerns us here. What interests us is that part of his argument relied on claims about the irreducibly subjective and, as a result, potentially alien nature of experience. Nagel assumed that bats, like all mammals, “have experience.” Experience, here, corresponds roughly to what philosophers call “phenomenal consciousness”, states that there is something it is like to be in. I take it to be roughly synonymous with sentience, too. Nagel wrote,

[T]he essence of the belief that bats have experience is that there is something it is like to be a bat. Now we know that most bats (the microchiroptera, to be precise) perceive the external world primarily by sonar, or echolocation, detecting the reflections, from objects within range, of their own rapid, subtly modulated, high frequency shrieks. Their brains are designed to correlate the outgoing impulses with the subsequent echoes, and the information thus acquired enables bats to make precise discriminations of distance, size, shape, motion, and texture comparable to those we make by vision. But bat sonar, though clearly a form of perception, is not similar in its operation to any sense that we possess, and there is no reason to suppose that it is subjectively like anything we can experience or imagine. This appears to create difficulties for the notion of what it is like to be a bat.

The bats, like all conscious creatures, “embody a particular point of view.” Their experience is only accessible from their point of view, Nagel thinks. And so it is inaccessible to us. We can’t know what it’s like to be a bat. If we could, we’d be bats, and so we wouldn’t be humans imagining what it’s like to be bats. So, to be more precise, we could know what bat consciousness is like, but only by adopting the bat’s first-person point of view, which we can’t. From the objective, or third-person, standpoint in general (and of physicalism in particular), we are missing the essential dimension of subjectivity. The problem generalizes beyond bats to all forms of subjective experience. We can similarly ask what it’s like to be a crow, an octopus, a hermit crab, or a bumblebee and find ourselves equally stumped. For that matter, human experience, if it is irreducibly subjective, as Nagel argues, is likewise inaccessible to the objective point of view. The roadblock is the same (language and shared experience definitely help in the case of humans).6

I don’t know if Nagel was right, as much as I admire his work and enjoy teaching this paper. But even if there was nothing intrinsically mysterious about bat consciousness, the fact remains: they go through the world very much unlike ourselves, despite sharing the same basic mammalian hardware. We have so much to learn from bats. And yet nobody knows what it’s like to be them. We have no idea what much of the world looks like. Isn’t that wonderful?

L. Greenspoon, E. Krieger, R. Sender, Y. Rosenberg, Y.M. Bar-On, U. Moran, T. Antman, S. Meiri, U. Roll, E. Noor, & R. Milo, The global biomass of wild mammals, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120 (10) e2204892120, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2204892120 (2023).

According to another PNAS study, there are approximately 50 billion birds (of approximately 92% of extant bird species). C.T. Callaghan, S. Nakagawa, & W.K. Cornwell, Global abundance estimates for 9,700 bird species, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 (21) e2023170118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023170118 (2021). I couldn’t find a reliable estimate of the total number of fish (individuals, not species) in the oceans, though the 3.5 trillion figure circulates online. It is at the very least in the order of three trillions—we kill between 1 and 3 trillion wild fish each year.

Egg-laying hens, because they’re exploited for their products rather than their meat, live longer than broiler chickens, which are raised for their meat and slaughtered as soon as they reach their optimal weight. Broilers are usually slaughtered at about seven weeks old in the US. Layers typically live about 1.5 years (sometimes up to 3).

Remember that we’re only talking about mammals. Comparing wild vs. domesticated birds or fish is even more complicated. Even though there was a mind-boggling total of over 25.6 billion individual poultry birds in 2018, wild birds still outnumber them by 2:1. It’s unlikely that farmed fish outnumber wild fish despite the depletion of “fishstocks”. The oceans are big.

Nagel, Thomas. “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” Philosophical Review 83 (1974): 435–50.

Nagel’s near-impossibility arguments have been notoriously challenged by Daniel Dennett, who passed away last year. Dennett developed “heterophenomenology” as a third-person method to investigate human consciousness and overcome the allegedly unbridgeable (illusory, to him) gap between subjective experience and objectivity. In fact, my sympathies more often lie with Dennett’s (I’m a naturalist, I’m not too worried about free will, consciousness-as-that-irreducible-thing is probably an illusion, among other things).

“Most mammals are bats” is definitely the coolest fact I’ve learned in a long time. As J. B. S. Haldane observed, the world isn’t just weirder than I imagine, it’s weirder than I can imagine. And he’d probably also be excited to learn that God is inordinately fond of bats as well as beetles.