The world is weird and wonderful. These are ineliminable features of the world, at least as long as creatures like us are around to contemplate it. Let me be pretentious and introduce a completely superfluous acronym. Call this the WWW thesis. If WWW is true, then any attempts to explain these features of the world away (as artifacts of our finite understanding, incomplete science, or relics of superstition or stupidity) are futile.

I’ll make up for the obnoxious formalism with cheesiness. What a wonderful world! We wonder at its weirdness and try to explain it. But also embrace the weirdness as a source of wonder for its own sake. Maybe the weirdness of the world doesn’t need to be explained away; explaining the world need not eliminate its weirdness or wonderfulness. Isn’t it weird that the relations between twelve arbitrary (and historically unstable) frequencies, their associated pitches (the twelve-tone chromatic scale), and their conventional arrangements (major, minor, and pentatonic scales, and other modes) generate some of the most incredible aesthetic and spiritual experiences?And that’s just the most common, not a unique way to carve out the sonic world in beauty-generating units! I mean, even Hanon can sound great:

How many possible worlds can you imagine where human beings never figured that out, let alone excelled at it, or where our auditory perception simply didn’t allow for such experiences? I can imagine a few and they all suck. Isn’t it wonderful that we happen to live in a world where that plus all the other things happen? Maybe what we need to jettison are the expectations that lead us to be bothered, rather than amazed, by weirdness.

Wonder is instrumental in discovery; it prompts us to better understand nature by uncovering its laws (or compiling the patterns and structures that underlie the fact that the world can make sense to us if you’re a Humean about the laws of nature). Wonder and its cognates—awe, admiration, amazement, puzzlement, surprise, curiosity—are also intrinsically valuable. The emotions of wonder and awe contribute to a flourishing life. A life devoid of such attitudes is bereft of intellectual thrill, antithetical to the childlike approach that many of us want to hold onto.

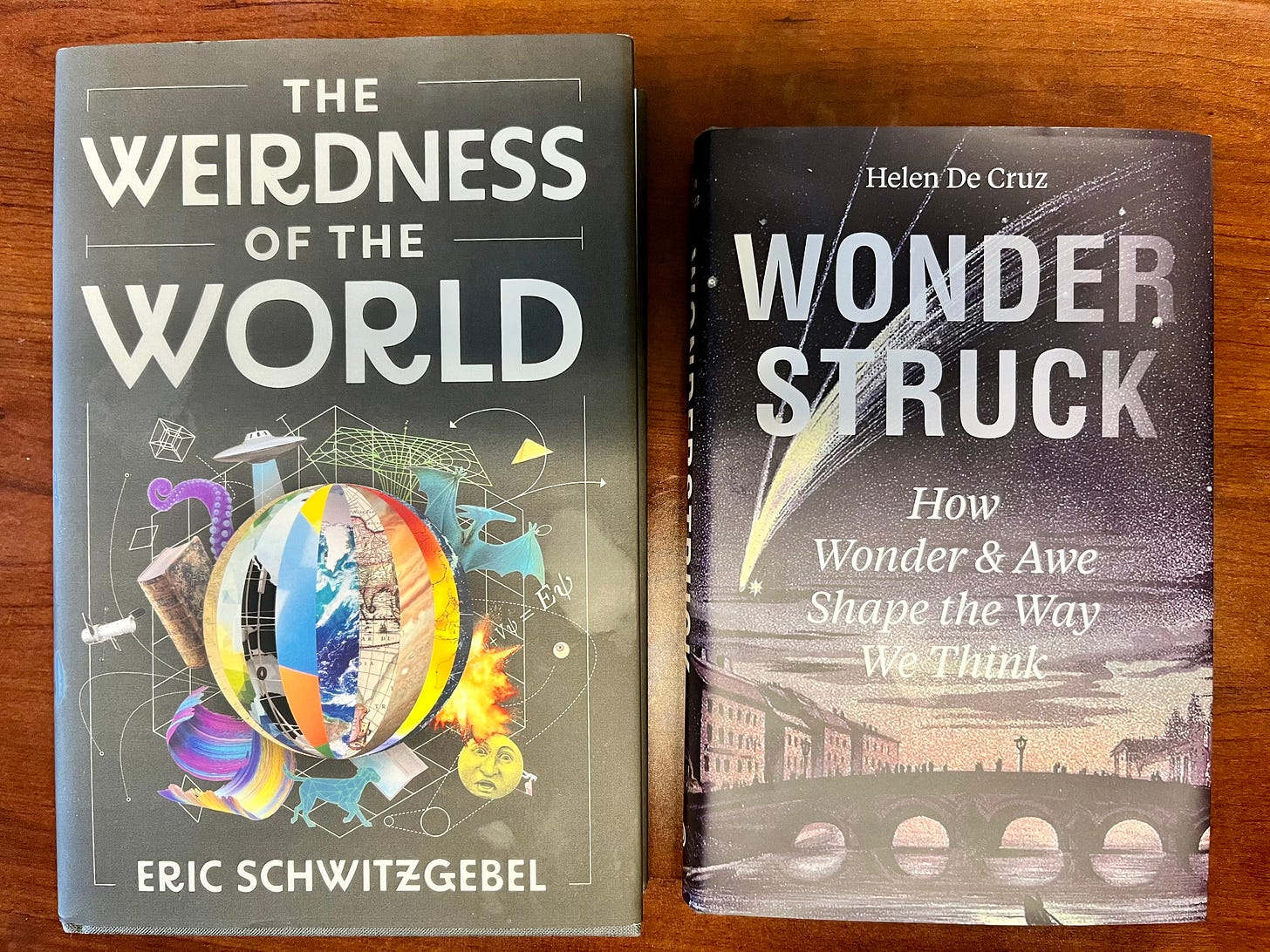

In what I want to believe is a wonderful coincidence, two philosophy books recently published by what is becoming my favorite academic publisher, Princeton University Press, adopt the childlike approach that motivates so much of art, religion, science, and philosophy. They are The Weirdness of the World by Eric Schwitzgebel and Wonderstruck: How Wonder & Awe Shape the Way We Think by Helen De Cruz (they both have great Substacks). I plan to incorporate a chapter from each book into my Intro to Philosophy (PHIL 101) this fall.

Aristotle famously wrote that philosophy begins in wonder, and De Cruz rightly makes much of this. Wonder was not just at its origins. It is at the beginning of every philosophical inquiry.

Human beings began to do philosophy even as they do now, because of wonder, at first because they wondered about the strange things right in front of them, and then later, advancing little by little, because they came to find greater things puzzling (Metaphysics 982b12).

The world is puzzling and strange and thus exerts pressure on our understanding, prompting us to interrogate it and do philosophy, which then and now also encompasses or spurs some important scientific questions. Just in case you’re feeling good about yourself today: Aristotle wrote some of the earliest and most important treatises in what was not yet physics, cosmology, biology (“natural history”), psychology, and political science, no less. Alexander the Great—legend has it—took time during his conquests to collect foreign animal specimens to bring back to his teacher, Aristotle. This was just a fraction of the hundreds of species that Aristotle examined, dissected, and classified, most of which were marine creatures, while wondering at their complexity and variety. Admittedly, he made some mistakes, such as calling the octopus “stupid”.

In her recent book, Justice for Animals, Martha Nussbaum builds her case upon the virtue of wonder, one of the virtues (alongside awe and compassion) that can take animals as its objects and, she argues, ground their recognition as subjects of justice. In this she is expanding on a point she already made in Frontiers of Justice back in 2006, where she wrote:

The capabilities approach judges instead, with the biologist Aristotle, that there is something wonderful and wonder-inspiring in all the complex forms of life in nature. In The Parts of Animals, Aristotle gives his students a lecture on why they should not “make a sour face” at the idea of studying animals, including the ones that seem not very exalted. … All animals are objects of wonder for the person who is interested in understanding. (p. 347-8)

And she goes on to quote Aristotle (p. 348):

We won’t leave out any of them if we can help it, whether more exalted or less exalted. For even in the case of those animals that give no delight to our senses, nature the artificer provides countless pleasures to those who can study the causes of things and who have a philosophical spirit … So we should not embark on the study of the less exalted animals with a childish disgust: for in everything in nature there is something wonder-inspiring. There is a story that some visitors once wanted to meet Heraclitus, and when they came in they found him warming himself in the kitchen. He told them, “Come in, don’t shrink back. There are gods here too.” So too, we should approach the study of each type of animal, not making a sour face, knowing that in every one of them is something natural and wonderful. (Parts of Animals 645a26–27)

In previous posts, I have tried to show that animals other than the usual suspects are amazing—absurd to us in some respect and yet sources of meaning and amazement.

Philosophy and biology, broadly construed, build off an initial sense of wonder. But the point is more general. It is often said that most of the natural sciences started in earnest when they branched off from philosophy—think of Galileo and Newton as natural philosophers, Adam Smith as philosopher and economist, William James as philosopher and psychologist (no, I’m not saying these guys literally invented those fields). Or Descartes’s contributions to mathematics and optics. Or Leibniz the polymath, who co-invented calculus (also credited to Newton) but also argued that the fundamental building blocks of reality are mind-like simple substances called “monads”. They are all featured in De Cruz’s Wonderstruck. The sciences inherit from philosophy its reflexive disposition to wonder—wonder how, wonder why, wonder at. Wonder and awe, De Cruz argues, are pretty much universal among human beings. They are manifested in distinctive but fundamentally common ways in the sciences, the arts, religion, and philosophy. There is admittedly a tension between science and wonder, or so we are sometimes told, following Max Weber—science promotes a “disenchanted” view of the world and is antithetical to the kind of wonder that religion and magic cultivate. But De Cruz dispels this myth that science and wonder are antithetical—in fact, Weber himself believed that disenchantment did not preclude re-enchantment. (I do not know my Weber well enough to tell whether he thought modern science would eventually undermine WWW in the scientific realm, if not in other domains.)

Weirdness is inescapable, argues Schwitzgebel (“Universal Dubiety” thesis), whenever we try to make sense of minds (are snails or the United States conscious?), knowledge (do we live in a dream or simulation?), and the fundamental structure of the world (quantum indeterminacy, superposition, entanglement, many-worlds, etc.). But weirdness arouses childlike wonder, an attitude we should cultivate, not only because it’s so much fun but because it leads to important insights, as Schwitzgebel muses near the end of his book.

To take one central source of weirdness, physics is indeed weird, and physicists don’t shy away from it, though some will minimize the weirdness and tell you to deal with it (the “Shut up and calculate” attitude allegedly promoted by the so-called “Copenhagen interpretation” of quantum mechanics, a misnomer for Niels Bohr’s camp). General relativity, quantum mechanics, black holes, and the Big Bang are all difficult to comprehend, and counterintuitive. Our evolved psychology, trained over millions of years to the macroscopic world in which things move at small scales and low velocities (compared to astronomical scales and the speed of light) is a poor match for the fundamental laws of the universe. And yet these are as mainstream and empirically successful theories as you’re going to get. If physics is weird but, by and large (if defeasibly and incompletely) correct about the laws of nature, then it seems we are forced to accept the weirdness of nature. Embrace it might be too much to ask: shutting up and calculating does not so much evoke enthusiastic study as blind obedience. Still, from weirdness you cannot conclude that anything is wrong, whether it leads you to keep probing (Einstein) or to move on (Bohr). The problem is not the world, it is—unfortunately but inevitably—you—until you stop seeing this as a problem but instead take it as a source of wonder. Einstein thought some implications of quantum mechanics were not just weird but problematic, but that doesn’t mean the problem was to be explained away; he just thought the theory must be incomplete. Whether or not he was right about that, the weirdness did arouse fundamental inquiry and some kind of wonder. Namely, going beyond simply calculating—not that there’s anything wrong with that.

What could be more suspicious than a world the scientific understanding of which perfectly lines up with our naive expectations? What an amazing coincidence that would be, a source of wonder on its own matched only by the serendipitous publication of these two books! Indeed, let me posit that such a coincidence would be even weirder—and much harder to explain scientifically—than whatever weirdness physics tells you is the case. To now make up for all the cheesiness, let me obnoxiously call this the Weirdness is Normal (WIN) conjecture. Since any formalism in this post is completely superfluous, that’s the last you’ll hear of this conjecture.

Science and philosophy are fun and all that, but they’re not all that important. And so I’m going to leave you with a truly bizarre and equally wonderful moment of music, an endless source of wonder if there ever was one. While music does not feature prominently in Wonderstruck, it is definitely in the background. De Cruz plays the lute and is especially interested in Renaissance and Baroque music. Watch her play Chaconne la comète, by Jacques de Gallot (1625-1695), a “musical rendition of the sighting of an unusually bright comet that passed across Europe and other parts of the world in the winter of 1680” at the link below:

The moment I want to focus on is, you guessed it, from Mozart (sorry, y’all Mozart-haters will have to either unsubscribe or shut up and listen!). In the last movement of his Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550, Mozart inserts what the conductor (and host of the marvelous Sticky Notes podcast) Joshua Weilerstein has dubbed “the most extraordinary moment of the piece” and “the classical music version of covfefe” in his episode on this symphony (he also has a mini-episode specifically dedicated to this moment but it’s restricted to Patreon supporters so I won’t share it). The moment comes in the last movement, after the repeat of the exposition. Here’s a video detailing the moment:

Weilerstein comments:

After that expression of unbridled joy, Mozart stops in his tracks, and writes the most harmonically adventurous music he would ever write in his huge output of music. In fact, in that passage, Mozart gives us 11 out of the 12 notes of the scale. The only one he avoids is a G - the home key of the movement. The G minor horse we’ve been riding has just thrown us off and has run off with all of tonality. Around 140 years later, Arnold Schoenberg would catch up to that horse, take its ideas, and usher in a new era of music when he took the central idea of this moment, a loss of tonal grounding and security, and spun it into a whole style of music, called 12 tone music. …

What this moment of craziness allows Mozart to do is to create an incredible sequence of harmonic changes. But unlike the changes in the first movement, which were based on the motive almost exclusively, this time Mozart uses his opening motive of the last movement and adds to it the main idea of those extraordinarily strange measures of the beginning of the development. …

And Mozart isn't done - remember that in the first and second movements, his developments were surprisingly short, and the movements were incredibly compact. In this last movement though, Mozart pulls out all the stops.

This moment doesn’t shock the modern ear, because we are now more accustomed to dissonance and atonality. And because it is one of Mozart’s most famous and beloved symphonies, it has just become familiar (though I suspect most people are familiar with the first movement and might overlook this wild allegro). But it is truly bizarre and out of its time. It is unexpected. Its role isn’t obvious. It’s also wonderful.

It’s one of Mozart’s weirdest moments but by no means the only one—Mozart gets the unfair reputation of being easy and repetitive, which only people who have never really listened can actually believe. And remember that in his final year, Mozart composed a pretty strange but of course widely admired opera titled The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte), K. 620. Setting aside the Masonic influence, the opera is often taken to also reflect the influence of the Enlightenment and its triumph over obscurantism. Hardly a condemnation of disenchanting science, you might think. But magic pervades the opera, it is not restricted to the dark forces of the Queen of the Night or more sunny forces of the high priest Sarastro. The opera contains many magical moments, but one of my favorites (and this is going to be cheesy) is the famous Papageno-Pamina duet in the finale, where the two lovers—astonished to see each other—engage in charming bird-like courting (“Pa-pa-pa”) (see an interesting note on the origins of the duet here; also, it bears some similarity to a Salieri opera).1 Now, I don’t believe in magic, but if anything ever comes close to making me doubt, Mozart will be one of the reasons.

Enjoy and wonder away!

Ultimate cheesy note: This is the music we played at my wedding ten years ago.

Wonderful the way you put these philosophers and books together here. Moving and much appreciated!